Newsletter

AUSSTELLUNG

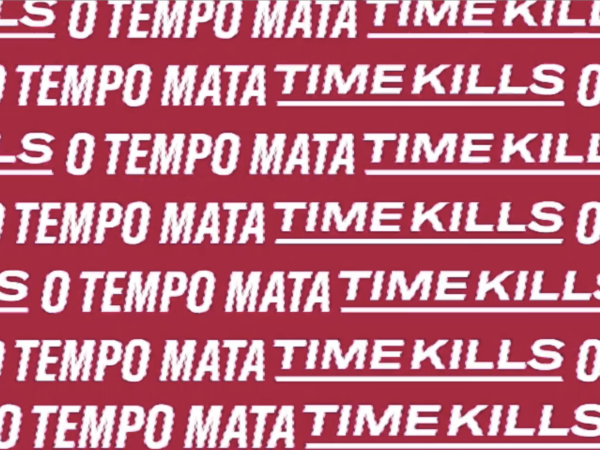

DOUBLE FEATURE: TAREK LAKHRISSI

JSF Berlin

6. Januar – 28. April 2024

CLOSE-UP – WERKE DER WOCHE

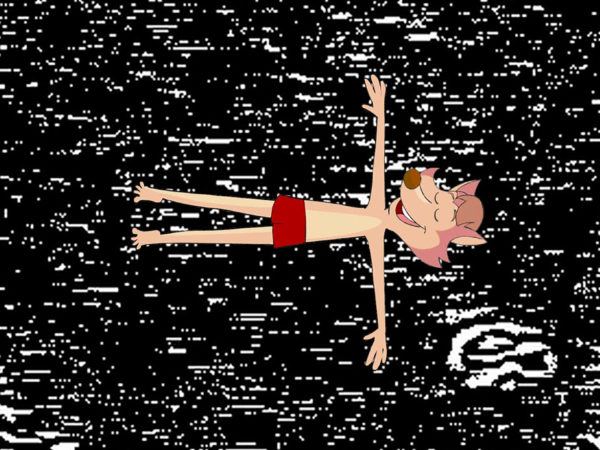

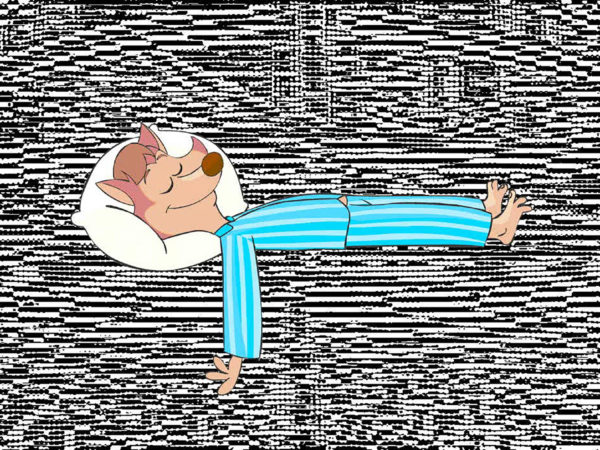

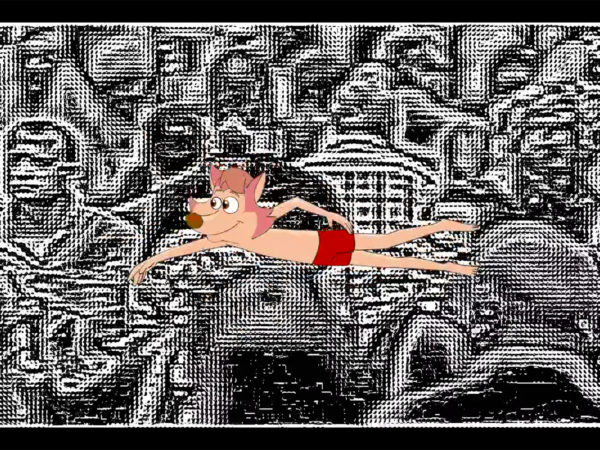

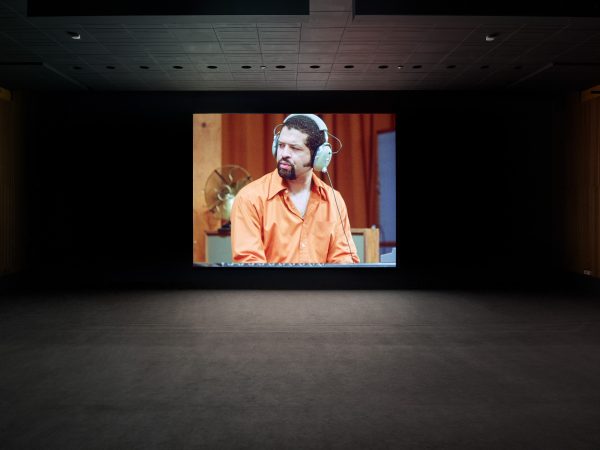

Young-jun Tak, Wish You a Lovely Sunday, 2021, Video, 18′38′′, Farbe, Ton.

AUSSTELLUNG

UNBOUND: PERFORMANCE AS RUPTURE

JSF Berlin

14. September 2023 – 28. Juli 2024

PERFORMANCE

(LA)HORDE, TO DA BONE

JSF Berlin

26.–27. April 2023

KONZERT

MATANA ROBERTS

JSF Berlin

10. Februar 2023

AUSSTELLUNG

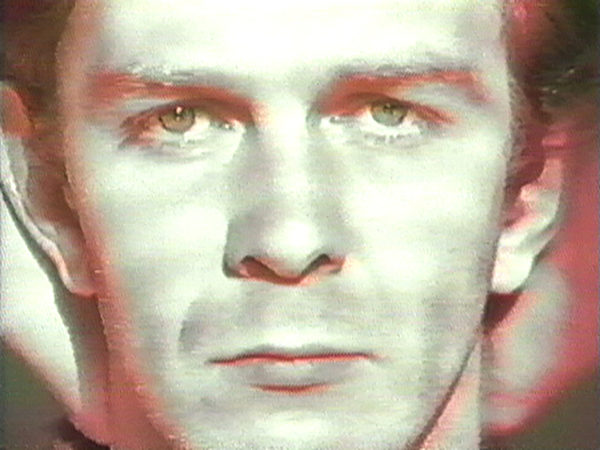

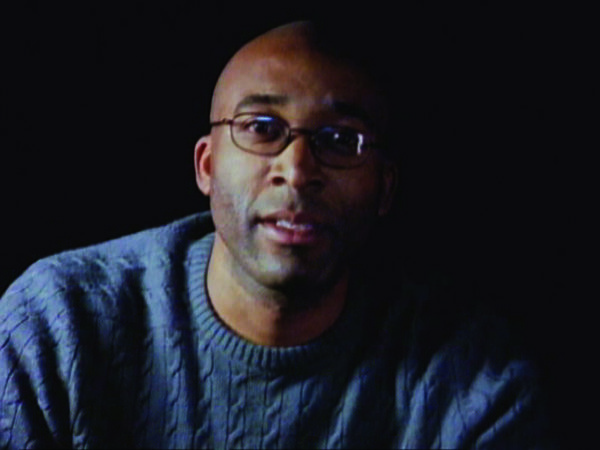

ULYSSES JENKINS: WITHOUT YOUR INTERPRETATION

JSF Berlin

11. Februar – 30. Juli 2023

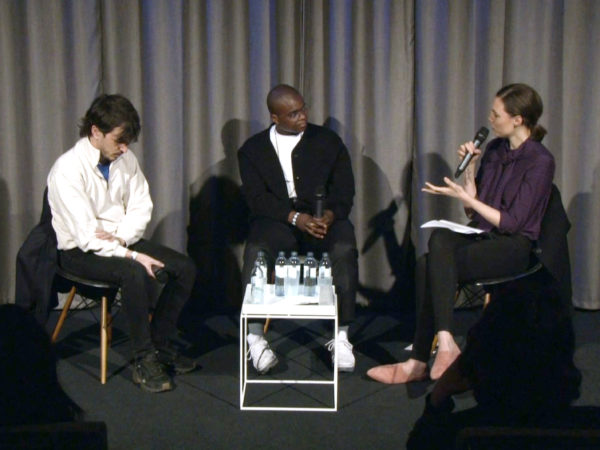

TALK

Stephanie Comilang und Simon Speiser im Gespräch mit Kuratorin Lisa Long

JSF Berlin

3. Dezember 2022

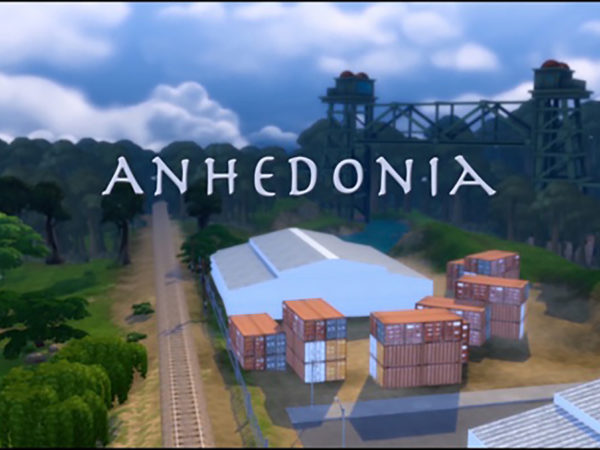

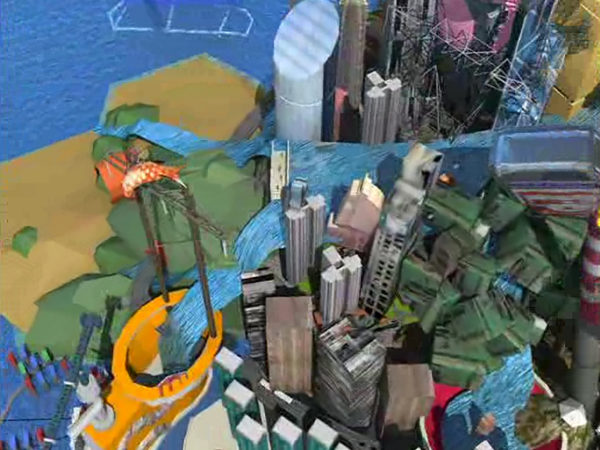

AUSSTELLUNG

WORLDBUILDING: VIDEOSPIELE UND KUNST IM DIGITALEN ZEITALTER

JSF Düsseldorf

5. Juni 2022 – 10. Dezember 2023

AUSSTELLUNG

STEPHANIE COMILANG & SIMON SPEISER: PIÑA, WHY IS THE SKY BLUE?

JSC Berlin

28. April – 4. Dezember 2022

TALK

James Richards im Gespräch mit der Kuratorin Lisa Long, JSC Berlin, 11. März 2022

JETZT ONLINE IN DER JSC VIDEO LOUNGE

Über 220 zeitbasierte Medienkunstwerke von über 60 Künstler*innen aus der JULIA STOSCHEK COLLECTION

CLOSE-UP – WERKE DER WOCHE

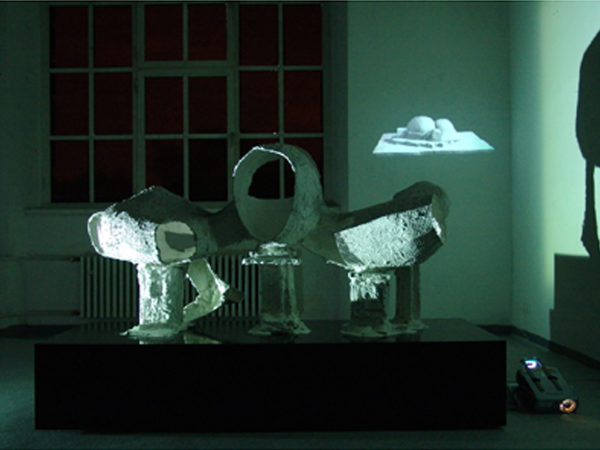

Imi Knoebel, Projektion X, 1972, Video

CLOSE-UP – WERKE DER WOCHE

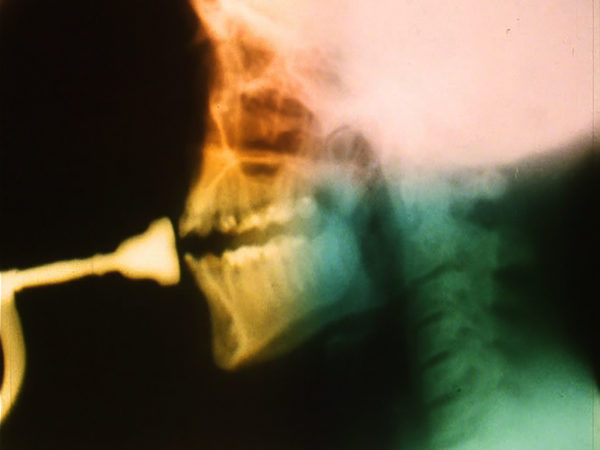

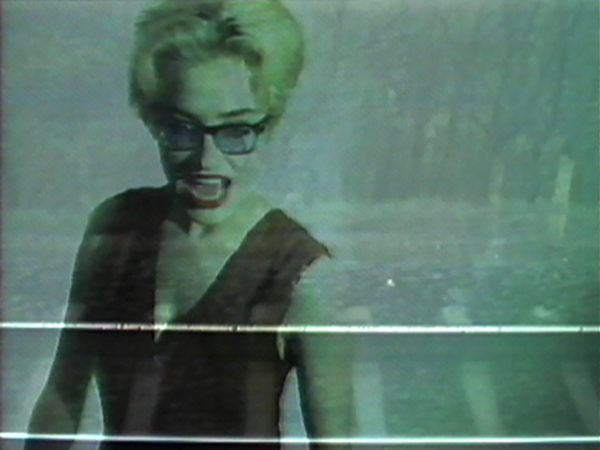

Barbara Hammer, X, 1975, 16-mm-Film, transferiert auf Video

CLOSE-UP – WERKE DER WOCHE

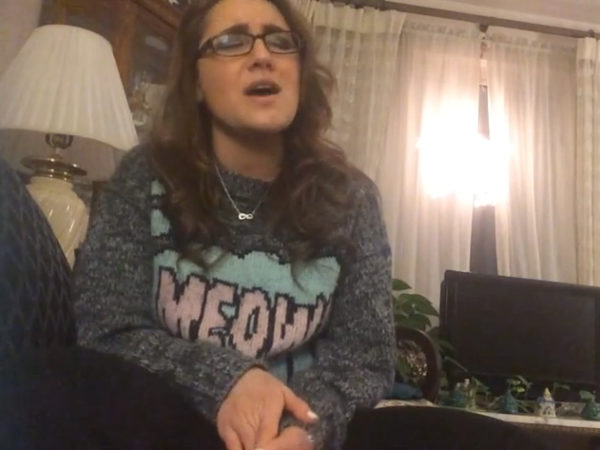

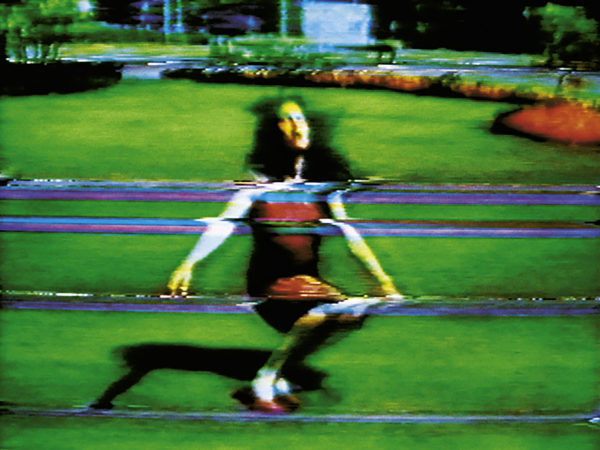

Ryan Trecartin, P.opular S.ky (section ish), 2009, HD-Video

AUSSTELLUNG

GENERATION LOSS – 10 JAHRE JULIA STOSCHEK COLLECTION, JSC Düsseldorf, 10. Juni 2017 – 9. September 2018

AUSSTELLUNG

MERIEM BENNANI: PARTY ON THE CAPS, HORIZONTAL VERTIGO

JSC Berlin

25. Januar – 29. November 2020

PERFORMANCE

COLIN SELF – SUBTEXT, HORIZONTAL VERTIGO

JSC Berlin

31. Mai – 1. Juni 2019

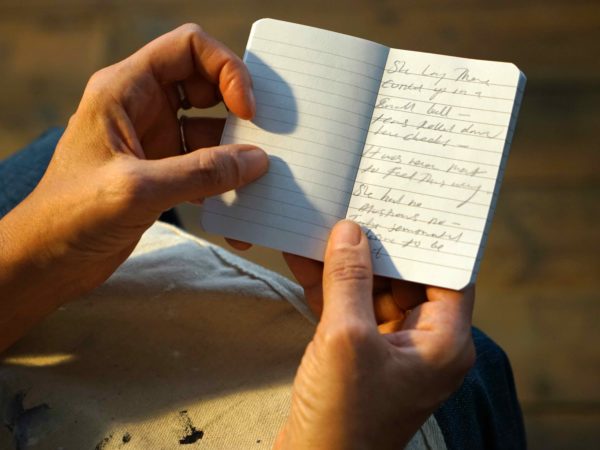

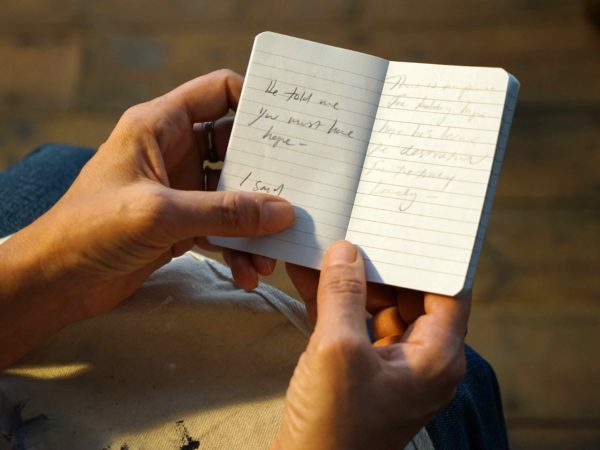

BASEL ABBAS & RUANNE ABOU-RAHME, THE INCIDENTAL INSURGENTS: THE PART ABOUT THE BANDITS (CHAPTER 2), 2012/13

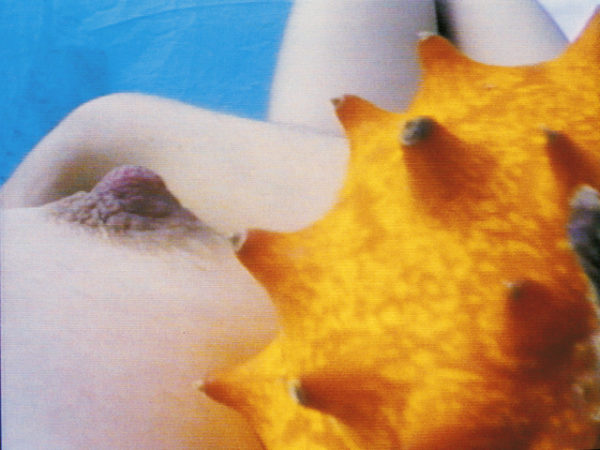

PIPILOTTI RIST, ALS DER BRUDER MEINER MUTTER GEBOREN WURDE, DUFTETE ES NACH WILDEN BIRNENBLÜTEN VOR DEM BRAUNGEBRANNTEN SIMS, 1992

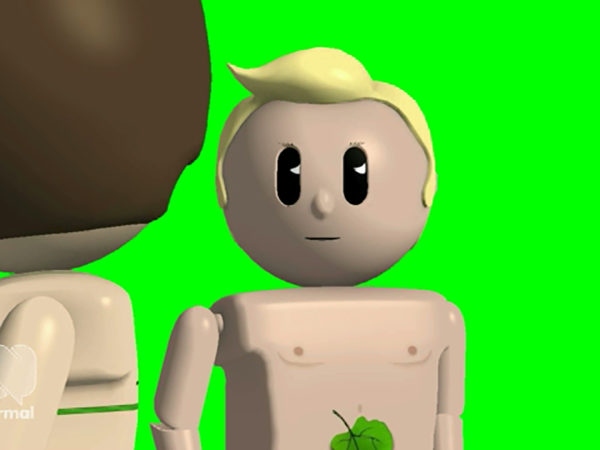

WORLDBUILDING: VIDEOSPIELE UND KUNST IM DIGITALEN ZEITALTER

JSF DÜSSELDORF, 5. JUNI 2022 – 10. DEZEMBER 2023

STEPHANIE COMILANG & SIMON SPEISER

PIÑA, WHY IS THE SKY BLUE?

JSC Berlin, 28. April – 4. Dezember 2022

JSC ON VIEW: MYTHOLOGISTS

WORKS FROM THE JULIA STOSCHEK COLLECTION

JSC DÜSSELDORF, 17. JANUAR – 19. DEZEMBER 2021

JSC ON VIEW: BASEL ABBAS & RUANNE ABOU-RAHME, THOMAS DEMAND, BEATRICE GIBSON, ARTHUR JAFA, SIGALIT LANDAU, ADAM MCEWEN, COLIN MONTGOMERY, TARYN SIMON, HITO STEYERL, TOBIAS ZIELONY

WORKS FROM THE JULIA STOSCHEK COLLECTION

JSC DÜSSELDORF, 9. FEBRUAR – 6. DEZEMBER 2020

JSC ON VIEW: LUTZ BACHER, BARBARA HAMMER, CAROLEE SCHNEEMANN

WORKS FROM THE JULIA STOSCHEK COLLECTION

JSC DÜSSELDORF, 21. JULI – 22. DEZEMBER 2019

PAULINE BOUDRY / RENATE LORENZ, ONGOING EXPERIMENTS WITH STRANGENESS

HORIZONTAL VERTIGO

JSC BERLIN, 26. APRIL – 28. JULI 2019

ARTHUR JAFA: A SERIES OF UTTERLY IMPROBABLE, YET EXTRAORDINARY RENDITIONS

JSC BERLIN, 11. FEBRUAR – 16. DEZEMBER 2018

GENERATION LOSS – 10 YEARS JULIA STOSCHEK COLLECTION

JSC DÜSSELDORF, 10. JUNI 2017 – 9. SEPTEMBER 2018

STEPHANIE COMILANG UND SIMON SPEISER IM GESPRÄCH MIT KURATORIN LISA LONG

JSC BERLIN, 3. DEZEMBER 2022

RINDON JOHNSON & EDUARDO WILLIAMS IM GESPRÄCH MIT DER KURATORIN LISA LONG

JSC DÜSSELDORF, 31. MÄRZ 2019

STEPHANIE COMILANG UND SIMON SPEISER IM GESPRÄCH MIT KURATORIN LISA LONG

JSC BERLIN, 3. DEZEMBER 2022

RINDON JOHNSON & EDUARDO WILLIAMS IM GESPRÄCH MIT DER KURATORIN LISA LONG

JSC DÜSSELDORF, 31. MÄRZ 2019

JULIA STOSCHEK SPRICHT ÜBER RMB CITY – A SECOND LIFE CITY PLANNING BY CHINA TRACY (2007) VON CAO FEI

JULIA STOSCHEK SPRICHT ÜBER THE INCIDENTAL INSURGENTS: THE PART ABOUT THE BANDITS (CHAPTER 2) (2012/13) VON BASEL ABBAS & RUANNE ABOU-RAHME

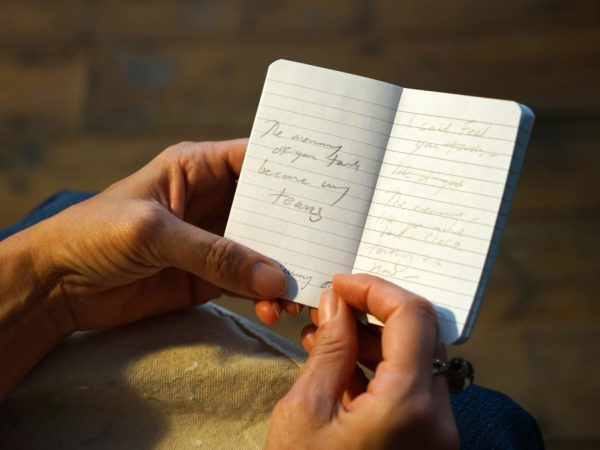

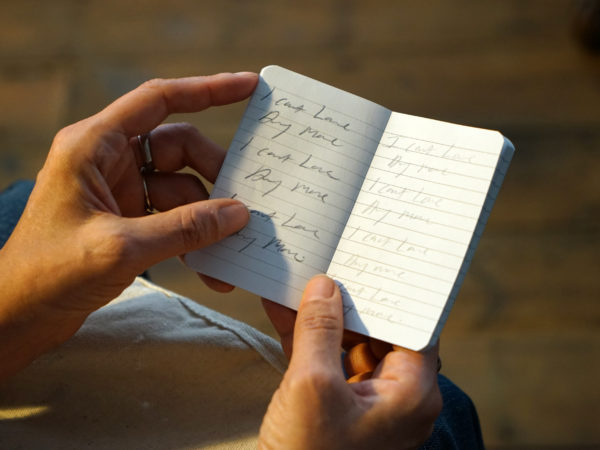

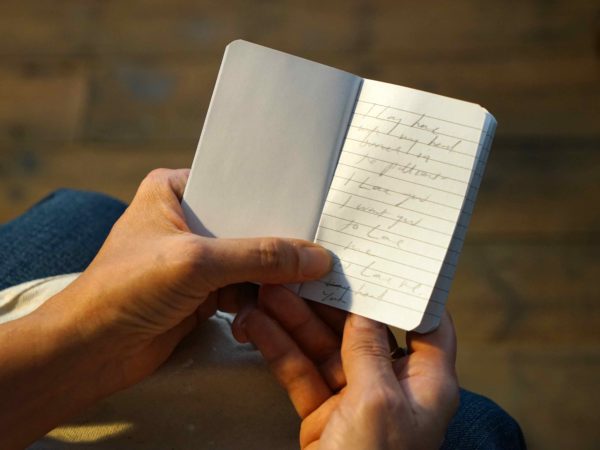

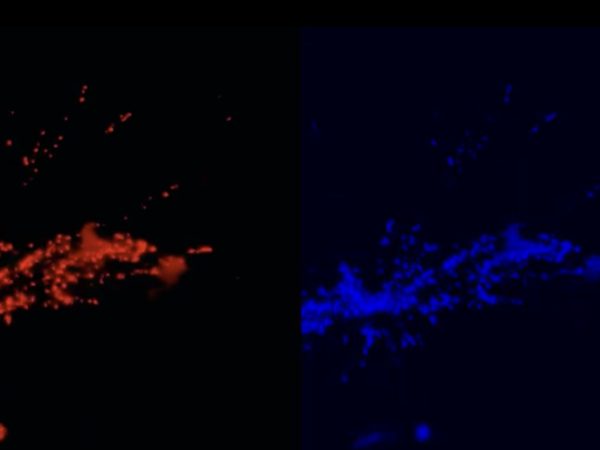

JACOLBY SATTERWHITE, SHRINES, 2020

JACOLBY SATTERWHITE, SHRINES, 2020

JACOLBY SATTERWHITE, SHRINES, 2020

JACOLBY SATTERWHITE, SHRINES, 2020

JACOLBY SATTERWHITE, SHRINES, 2020

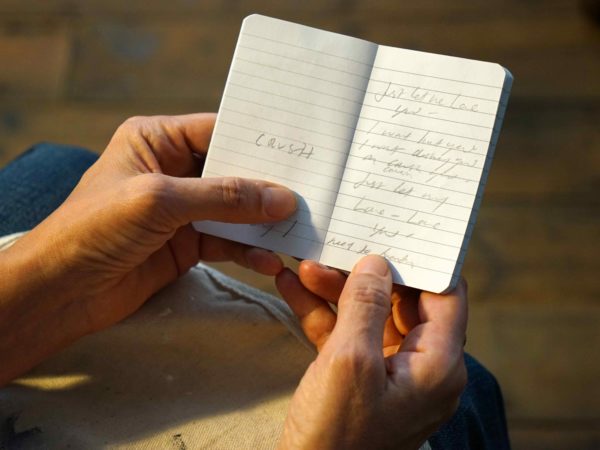

BASEL ABBAS & RUANNE ABOU-RAHME, THE INCIDENTAL INSURGENTS: THE PART ABOUT THE BANDITS (CHAPTER 2), 2012/13

BASEL ABBAS & RUANNE ABOU-RAHME, THE INCIDENTAL INSURGENTS: THE PART ABOUT THE BANDITS (CHAPTER 2), 2012/13

BASEL ABBAS & RUANNE ABOU-RAHME, THE INCIDENTAL INSURGENTS: THE PART ABOUT THE BANDITS (CHAPTER 2), 2012/13

BASEL ABBAS & RUANNE ABOU-RAHME, THE INCIDENTAL INSURGENTS: THE PART ABOUT THE BANDITS (CHAPTER 2), 2012/13

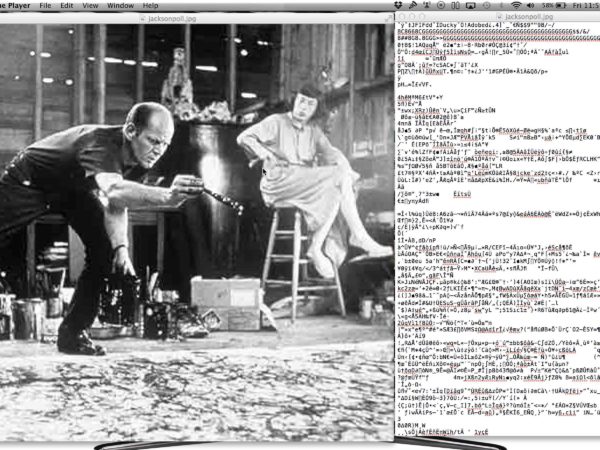

The Incidental Insurgents: The Part About the Bandits (Chapter 2) Courtesy of the artists. Courtesy of the artists. 2012/13The Part About the Bandits (2012/13) ist der erste Teil des dreiteiligen, vielschichtigen Projekts The Incidental Insurgents (dt.: Die zufälligen Rebellen) und besteht aus zwei Kapiteln. Das Künstler*induo untersucht in den beiden sich ergänzenden Kapiteln seine*ihre eigene Position als Künstler*in sowie die Überwindung politischer Radikalität. Das erste Kapitel umfasst eine multimediale Installation, die sich der Ermittlung von vier unterschiedlichen Leben echter und erfundener politischer Rebell*innen oder Bandit*innen widmet. Das zweite Kapitel besteht aus einer Videoarbeit, die mit pulsierendem Text in englischer sowie arabischer Sprache überlagert ist. Zu sehen sind zwei von hinten gefilmte Personen in einem Auto auf Straßen und Gebieten rund um das Westjordanland. Sie scheinen in einer eingegrenzten, ausweglosen und – verstärkt durch Text und Ton – bedrohlichen Gegenwart gefangen zu sein. Die Protagonist*innen im ersten Teil der Arbeit führen den Betrachter*innen die Unzulänglichkeit der politischen Ausdrucksmöglichkeiten vor Augen. So offenbaren sie die aktuelle Suche nach einer neuen politischen Sprache, einem neuen Imaginären sowie Visionen der Zukunft.

Jasmin Klumpp

The Part About the Bandits (2012–13), the first part of the complex, three-part project The Incidental Insurgents, consists of two chapters. In both of the complimentary chapters the artist duo examines its own position as artists as well as the eclipsing of political radicality. The first chapter is a multimedia installation that investigates four different lives of fictitious and real political rebels or bandits. The second chapter is a video piece, which is overlaid with pulsating text in Arabic and English. It shows two people in a car who have been filmed from behind on streets and locations around the West Bank. They seem to be caught in an enclosed, futile, and—heightened by the text and sound— threatening present. The various protagonists in the first part of the piece make viewers aware of the inadequacy of the political possibilities of expression. In this way they reveal the contemporary search for a new political language, new imagination, and visions of the future.

Jasmin Klumpp

Basel Abbas & Ruanne Abou-Rahme Basel Abbas & Ruanne Abou-RahmeDie palästinensischen Künstler*innen Basel Abbas und Ruanne Abou-Rahme befassen sich in ihrem Œuvre mit den Themen Politik und Kultur, mit Fragen zu Begehren, Desaster, Subjektivität und Absurditäten aktueller Machtpraktiken. Sie kreieren audio-visuelle Live-Performances und interdisziplinäre Installationen, um Optionen der Gegenwart neu zu gestalten. In ihren Arbeiten stellen die Künstler*innen bereits vorhandenes und selbst produziertes Material in Form von Musik, Sound, Bild, Text, Installation und performativen Praktiken zusammen. Mittels fiktiver, realer, teils historischer Erzählungen, Figuren, Objekten, Gesten und Orten entwickeln Abbas und Abou-Rahme neue, fragmentarische „Skripte“, die Realität und Imagination in Bezug zueinander setzen.

Jasmin Klumpp

Künstlerduo, bestehend aus:

Palestinian artists Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme examine the subjects of politics and culture, and questions of desire, disaster, subjectivity, and absurdities of current approaches to power in their work. They create audiovisual live performances and interdisciplinary installations to rethink options for the present. In their works, the artists present found footage and material that they have produced themselves in the form of music, sound, images, texts, installations, and performative approaches. Using fictitious, real, and partly historical narratives, figures, objects, gestures, and places, Abbas and Abou-Rahme develop new fragmentary “scripts” that link reality and imagination to each other.

Jasmin Klumpp

Artist duo, consisting of:

8878 4066 4051 4059 11381BASEL ABBAS & RUANNE ABOU-RAHME, THE INCIDENTAL INSURGENTS: THE PART ABOUT THE BANDITS (CHAPTER 2), 2012/13

ANICKA YI, THE FLAVOR GENOME, 2016

ANICKA YI, THE FLAVOR GENOME, 2016

ANICKA YI, THE FLAVOR GENOME, 2016

ANICKA YI, THE FLAVOR GENOME, 2016

The Flavor Genome Videostill. Courtesy of the artist and 47 Canal, New York and Gladstone Gallery, New York/Brussels. Video still. Courtesy of the artist and 47 Canal, New York and Gladstone Gallery, New York/Brussels. 2016 Yi Anicka 4376 4066 4051 4049 4059ANICKA YI, THE FLAVOR GENOME, 2016

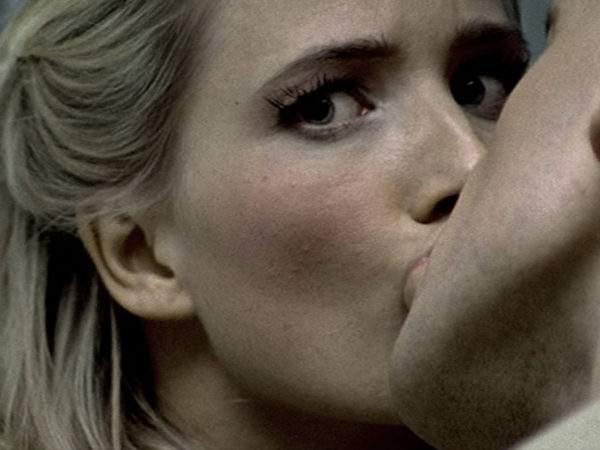

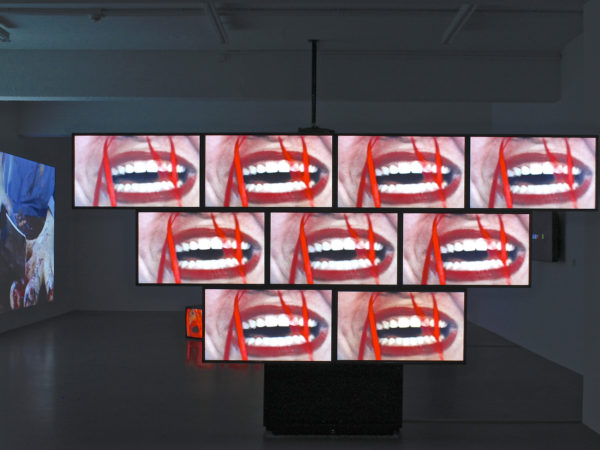

ANNE IMHOF, UNTITLED WAVE, 2021

ANNE IMHOF, UNTITLED WAVE, 2021

ANNE IMHOF, UNTITLED WAVE, 2021

ANNE IMHOF, UNTITLED WAVE, 2021

Untitled Wave 2021 Imhof Anne 4243ANNE IMHOF, UNTITLED WAVE, 2021

ILIT AZOULAY, OBJECT #1, 2015

ILIT AZOULAY, OBJECT #1, 2015

ILIT AZOULAY, OBJECT #1, 2015

ILIT AZOULAY, OBJECT #1, 2015

Object #1 Courtesy of the artist and Daata, London. Courtesy of the artist and Daata, London. 2015Während des israelischen Unabhängigkeitskrieges 1948 musste der palästinensische Teil der Einwohner*innen Jaffas die Stadt verlassen. Die meisten der geräumten Häuser wurden dann an jüdische, meist aus Marokko stammende, Migranten*innen übergeben, um diesen schnell ein Dach über dem Kopf zu geben. Einige der Gebäude blieben jedoch völlig unangetastet. In ihnen finden sich noch heute alle zurückgelassenen Habseligkeiten, wie Möbel, Kleider, Bücher und andere persönliche Dinge.

Ilit Azoulay

During Israel’s 1948 Independence War, Palestinians were forced to leave their houses in Jaffa. Later on, most of the remained houses were given to Jewish immigrant families, mostly from Morocco, as a prompt housing solution. Some of the houses were left untouched, with all that was left behind – furniture, clothes, books, personal belongings.

Ilit Azoulay

Azoulay Ilit 4145 4066 4046 4059 12509 11381ILIT AZOULAY, OBJECT #1, 2015

ILIT AZOULAY, OBJECT #3, 2015

ILIT AZOULAY, OBJECT #3, 2015

ILIT AZOULAY, OBJECT #3, 2015

ILIT AZOULAY, OBJECT #3, 2015

Object #3 Courtesy of the artist and Daata, London. Courtesy of the artist and Daata, London. 2015Während des israelischen Unabhängigkeitskrieges 1948 musste der palästinensische Teil der Einwohner*innen Jaffas die Stadt verlassen. Die meisten der geräumten Häuser wurden dann an jüdische, meist aus Marokko stammende, Migranten*innen übergeben, um diesen schnell ein Dach über dem Kopf zu geben. Einige der Gebäude blieben jedoch völlig unangetastet. In ihnen finden sich noch heute alle zurückgelassenen Habseligkeiten, wie Möbel, Kleider, Bücher und andere persönliche Dinge.

Ilit Azoulay

During Israel’s 1948 Independence War, Palestinians were forced to leave their houses in Jaffa. Later on, most of the remained houses were given to Jewish immigrant families, mostly from Morocco, as a prompt housing solution. Some of the houses were left untouched, with all that was left behind – furniture, clothes, books, personal belongings.

Ilit Azoulay

Azoulay Ilit 4145 4066 4046 4059 12509 11381ILIT AZOULAY, OBJECT #3, 2015

ILIT AZOULAY, OBJECT #4, 2015

ILIT AZOULAY, OBJECT #4, 2015

ILIT AZOULAY, OBJECT #4, 2015

ILIT AZOULAY, OBJECT #4, 2015

Object #4 Courtesy of the artist and Daata, London. Courtesy of the artist and Daata, London. 2015Während des israelischen Unabhängigkeitskrieges 1948 musste der palästinensische Teil der Einwohner*innen Jaffas die Stadt verlassen. Die meisten der geräumten Häuser wurden dann an jüdische, meist aus Marokko stammende, Migranten*innen übergeben, um diesen schnell ein Dach über dem Kopf zu geben. Einige der Gebäude blieben jedoch völlig unangetastet. In ihnen finden sich noch heute alle zurückgelassenen Habseligkeiten, wie Möbel, Kleider, Bücher und andere persönliche Dinge.

Ilit Azoulay

During Israel’s 1948 Independence War, Palestinians were forced to leave their houses in Jaffa. Later on, most of the remained houses were given to Jewish immigrant families, mostly from Morocco, as a prompt housing solution. Some of the houses were left untouched, with all that was left behind – furniture, clothes, books, personal belongings.

Ilit Azoulay

Azoulay Ilit 4145 4066 4046 4059 12509 11381ILIT AZOULAY, OBJECT #4, 2015

ILIT AZOULAY, OBJECT #5, 2015

ILIT AZOULAY, OBJECT #5, 2015

ILIT AZOULAY, OBJECT #5, 2015

ILIT AZOULAY, OBJECT #5, 2015

Object #5 Courtesy of the artist and Daata, London. Courtesy of the artist and Daata, London. 2015Während des israelischen Unabhängigkeitskrieges 1948 musste der palästinensische Teil der Einwohner*innen Jaffas die Stadt verlassen. Die meisten der geräumten Häuser wurden dann an jüdische, meist aus Marokko stammende, Migranten*innen übergeben, um diesen schnell ein Dach über dem Kopf zu geben. Einige der Gebäude blieben jedoch völlig unangetastet. In ihnen finden sich noch heute alle zurückgelassenen Habseligkeiten, wie Möbel, Kleider, Bücher und andere persönliche Dinge.

Ilit Azoulay

During Israel’s 1948 Independence War, Palestinians were forced to leave their houses in Jaffa. Later on, most of the remained houses were given to Jewish immigrant families, mostly from Morocco, as a prompt housing solution. Some of the houses were left untouched, with all that was left behind – furniture, clothes, books, personal belongings.

Ilit Azoulay

Azoulay Ilit 4145 4066 4046 4059 12509 11381ILIT AZOULAY, OBJECT #5, 2015

ILIT AZOULAY, OBJECT #6, 2015

ILIT AZOULAY, OBJECT #6, 2015

ILIT AZOULAY, OBJECT #6, 2015

ILIT AZOULAY, OBJECT #6, 2015

Object #6 Courtesy of the artist and Daata, London. Courtesy of the artist and Daata, London. 2015Während des israelischen Unabhängigkeitskrieges 1948 musste der palästinensische Teil der Einwohner*innen Jaffas die Stadt verlassen. Die meisten der geräumten Häuser wurden dann an jüdische, meist aus Marokko stammende, Migranten*innen übergeben, um diesen schnell ein Dach über dem Kopf zu geben. Einige der Gebäude blieben jedoch völlig unangetastet. In ihnen finden sich noch heute alle zurückgelassenen Habseligkeiten, wie Möbel, Kleider, Bücher und andere persönliche Dinge.

Ilit Azoulay

During Israel’s 1948 Independence War, Palestinians were forced to leave their houses in Jaffa. Later on, most of the remained houses were given to Jewish immigrant families, mostly from Morocco, as a prompt housing solution. Some of the houses were left untouched, with all that was left behind – furniture, clothes, books, personal belongings.

Ilit Azoulay

Azoulay Ilit 4145 4066 4046 4059 12509 11381ILIT AZOULAY, OBJECT #6, 2015

HEIKE BARANOWSKY, GRAS, 2001

HEIKE BARANOWSKY, GRAS, 2001

HEIKE BARANOWSKY, GRAS, 2001

HEIKE BARANOWSKY, GRAS, 2001

Gras © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2021. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Barbara Weiss, Berlin. © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2021. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Barbara Weiss, Berlin. 2001Im Jahr 1503 malte Albrecht Dürer Das Große Rasenstück, das aufgrund des sachlichen Blicks auf ein Naturdetail als ein Meilenstein des Realismus in der Renaissance gilt. Ein halbes Jahrtausend später realisierte Heike Baranowsky Gras (2001), das aus einer ähnlichen Froschperspektive das Wedeln von Grashalmen im Wind festhält. Ganz anders als bei Dürer schafft jedoch Baranowskys Nahaufnahme keinen Überblick und keine naturwissenschaftlich geprägte Erkenntnis: Das Gras bewegt sich in einer geschmeidigen, beinah hypnotischen Schwingung und lässt sich nie fixieren. Der Blick ist hier also in keiner Weise einfrierend oder analytisch, sondern vielmehr haltlos und wiegt, dem unregelmäßigen Rhythmus der Pflanzen folgend, den Betrachter in eine meditative Trance.

Dr. Emmanuel Mir

In 1503 Albrecht Dürer painted Das Große Rasenstück (The Great Piece of Turf), which is considered a milestone of realism in the Renaissance for its objective perspective of something natural. Around five hundred years later Heike Baranowsky completed Gras (Grass; 2001), which captures the waving of grass in the wind from a similar worm’s eye view. However, unlike the Dürer, Baranowsky’s closeup does not provide an overview or any scientific insight: the grass undulates in a lithe, almost hypnotic motion, never allowing itself to come completely into focus. In other words, our gaze does not by any means capture or analyse, but is rather disoriented and sways us into a meditative trance by following the irregular rhythm of the grass.

Dr. Emmanuel Mir

Baranowsky Heike 4151 4065 4051 4049 4059 11381HEIKE BARANOWSKY, GRAS, 2001

HEIKE BARANOWSKY, MONDFAHRT, 2001

HEIKE BARANOWSKY, MONDFAHRT, 2001

HEIKE BARANOWSKY, MONDFAHRT, 2001

HEIKE BARANOWSKY, MONDFAHRT, 2001

Mondfahrt © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2021. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Barbara Weiss, Berlin. © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2021. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Barbara Weiss, Berlin. 2001Der Mond wird in vielen Kulturen der Welt verehrt: in Ägypten mit der Mondgöttin Isis, im antiken Rom war es Luna, nach der heute noch der erste Tag der Woche in Lehnübersetzung aus dem Lateinischen dies lunae, Mon(d)tag heißt. Auch in japanischen Shinto-Schreinen ist der Herrscher über die Nacht und „Mondzähler“ Tsukiyomi prominent vertreten, während die Azteken Tecciztecatl für sein Licht im Dunkel der Nacht dankten. Trotz dieser rituellen Bedeutung konnte wissenschaftlich bisher kein direkter Einfluss des Mondes auf die Menschen und andere Lebewesen der Erde nachgewiesen werden: Nur einige Zugvögel und bestimmte nachtaktive Insekten orientieren sich in ihrer Navigation am Stand der Mondscheibe.

In Heike Baranowskys Videoinstallation Mondfahrt aus dem Jahre 2001 bietet der Erdtrabant denkbar wenig Möglichkeit zur Orientierung. Vielmehr schwankt er selbst über den Nachthimmel, wie ein Betrunkener, der den Heimweg nicht mehr findet. Er verschwindet nie aus dem projizierten Bildrahmen und huscht tänzelnd beschwingt, dann zögerlich tastend, wie ein Suchscheinwerfer über die Wand. Er findet keinen Halt und bietet auch keinen, er hat seine feste, seit Menschengedenken vertraute Bahn verlassen. Aber wie wurde die kosmische Ordnung aufgehoben? Wie kommt es zu dieser seltsamen Bewegung? Die Erklärung ist denkbar einfach. Die Künstlerin hat ihre Filmaufnahmen an Bord einer Fähre gemacht, zwischen dem englischen Harwich und Hamburg. In einer Vollmondnacht richtete sie ihre Kamera auf den Mond ein und fixierte sie. Die Animation des Himmelskörpers besorgte das Rollen des Schiffes und die Bewegungen aufgrund des Seegangs. Nicht das Motiv bewegt sich, sondern die Kamera.

Durch die Bewegungen ist die romantische Gravitas des Mondes verloren, die zu sehnsüchtigen Kunstwerken inspirierte, von Figuren in den Bildern Caspar David Friedrichs bis zum Blue Moon, den Elvis Presley flehend ansang. Stattdessen hüpft und eiert der Erdtrabant mit unsteter Rhythmik im festgelegten Spielfeld der projizierten Bildfläche, und eignet sich so kaum mehr zu romantischen Betrachtungen. Vielmehr werden die Betrachter*innen auf sich selbst zurückgeworfen und ihre subjektive Perspektive – was bewegt den Mond wirklich?

Hier geht es weniger um Gravitas als um Gravitation: die Künstlerin hat eine kleine konzeptuelle Schleife angelegt. Der Mond ist nicht ganz unschuldig an den Bewegungen des Schiffes. Denn der Wellengang, der die Kamera in ihr eigentümliches Schwanken versetzt, wird zwar hauptsächlich durch Wind verursacht, aber auch durch die Gezeiten. Und die unterliegen wiederum der Anziehungskraft des Mondes. Der Kreis vollendet sich, der Mond bewegt das Schiff, die Kamera und endlich in der Projektion sich selbst.

Diese Erkenntnis ist ernüchternd und kann die Anziehungskraft der Videobilder nicht richtig erklären. Viele Videoarbeiten von Heike Baranowsky wirken in ihrer formalen Reduktion hermetisch, kühl und emotionslos. Die oft recht kurzen Aufnahmesequenzen, mit charakteristisch unbewegtem Blick, zeigen alltägliche Motive und wurden von ihr zu Endlosschleifen arrangiert. Durch die präzise Montage von vorwärts und rückwärts laufenden Bildern gelingt es der Künstlerin, den eingefangenen Moment nicht einzufrieren, sondern in andauernder Wiederholung in die Ewigkeit auszudehnen. Die dokumentarische Nüchternheit ihrer Bilder kontrastiert mit der den Wiederholungen inhärenten Geometrie und thematisiert so die trügerische Differenz zwischen Wirklichkeit und Natur, ihrer technisch-künstlerischen Abbildung im Video und unserer eigenen, aus unserer Erfahrung als normal und richtig wertenden Wahrnehmung.

Als Ausgangspunkt dienen dabei meist zeitliche Rhythmen, die Baranowsky immer wieder zu neuen, komplexen und überraschenden Figuren montiert, wie ihr Videotriptychon Radfahrer (Hase und Igel) aus dem Jahr 2000. Es zeigt in drei nebeneinander angeordneten Projektionsflächen zwei identisch aussehende Fahrradfahrer, die auf einer Radrennbahn ihre Kreise ziehen. Exakt die gleiche Sequenz wird jeweils in unterschiedlichen Tempi gezeigt: rechts in der realen Zeit, in der Mitte um zehn Prozent und links um zwanzig Prozent verlangsamt. Im Gesamtbild ist kaum noch auszumachen, dass die Videos in unterschiedlichen Geschwindigkeiten abgespielt werden. Stattdessen entsteht die Illusion eines unmöglichen Kontinuums, als könnten die Radfahrer von einer Projektion in die nächste fahren und sich sogar selbst überholen.

In Wirklichkeit findet das Rennen nur im Auge der Betrachter*innen statt, die die Fragmente selbst zusammenfügen. Nicht von ungefähr ist die Arbeit schon im Titel an das bekannte Märchen angelehnt, in dem der hochmütige Hase auf die List zweier identischer Igel hereinfällt.

Im sinnlosen Loop eines nicht endenden Wettlaufs gefangen, wird er Opfer seiner oberflächlichen Wahrnehmung. Das volkstümlich überlieferte Märchen wurde 1840 vom Mundartdichter Wilhelm Schröder veröffentlicht, mit den einleitenden Worten: „Diese Geschichte ist lügenhaft zu erzählen, Jungens, aber wahr ist sie doch, denn mein Großvater, von dem ich sie habe, pflegte immer, wenn er sie erzählte, dabei zu sagen: Wahr muss sie doch sein, mein Junge, sonst könnte man sie ja nicht erzählen.“

Heike Baranowsky ist weniger darauf aus, die Unterschiede zwischen wahr und falsch anzuprangern oder gar ein moralisches Urteil zu fällen. Vielmehr fordert sie die Fähigkeiten des Auges heraus, das Fantastische und das Unwahrscheinliche auch in der realistischen Vorstellung zu erkennen. Dazu bedient sie sich bestechend alltäglicher Motive, wie des Mondes, Radrennfahrern oder einer Schwimmerin im Schwimmbecken. Aber die Schwimmerin holt niemals Luft und kommt nie am Beckenrand an, die Fahrradfahrer scheinen die Dimensionen von Raum und Zeit überwinden zu können, und der Mond setzt sich über die kosmische Ordnung hinweg.

Dazu passt, dass der Titel der Arbeit Mondfahrt auch die kurze Geschichte der Mondlandung heraufbeschwört und die damit verbundenen Verschwörungstheorien, nach denen die Mondfahrt nie stattgefunden habe, sondern als in Hollywood Studios gedrehtes Ereignis sich nur medial abgespielt habe. Heike Baranowsky ist raffinierter und präziser in ihrem Werk, sie beschränkt sich auf einfache, beinahe schematische Abläufe und schließt sie zu einem Kreis zusammen. In der Wiederholung ereignet sich das Unmögliche, und tut es immer wieder. Das System ist modellhaft, die hypnotische Wiederholung des Gleichen, in geometrischen Variationen digitaler Schnittmuster. Dabei bringt die Künstlerin in einem rein formalen Spiel der Brechungen, Spiegelungen und Umkehrungen die möglichen Bedeutungen ins Schlingern, wie den Mond auf seiner ebenso eigenwilligen wie einsamen Bahn – und in seinem Gefolge die Betrachter*innen.

Angela Rosenberg

The moon is revered in many cultures of the world. In Egypt, Isis was the lunar deity, while in ancient Rome it was Luna, after whom the first day of the week was named: Monday comes from the Latin dies lunae, or “moon day.” In Japan, the ruler over the night and “Moon Reader” Tsukuyomi is prominently represented in Shinto shrines, and the Aztecs thanked Tecciztecatl for providing light in the darkness of night. Despite these beliefs, no direct influence of the moon on human beings or other forms of earthly life has ever been scientifically proven; only a few migratory birds and certain nocturnal insects orient themselves on the basis of the location of the lunar disk.

The earth’s satellite provides very few opportunities for orientation in Heike Baranowsky’s video installation Mondfahrt (Lunar Journey) of 2001. Instead, the moon sways over the nocturnal sky like a drunkard who cannot find his way home. Clearly placed in the image, its surface is easily recognizable, and it never disappears from the picture frame; as a projection on the wall, it just moves with curiously dancelike movements, sometimes exhilarated, and often quivering or groping like a searchlight. It finds no footing and also does not provide any; here it has left the fixed and familiar orbit it has had since time immemorial. But how is it that the cosmic order has been rescinded? How does this bizarre movement come about?

The explanation is remarkably simple. The artist recorded her film while aboard a ferry traveling from the English port town of Harwich to Hamburg. During a full moon night, she directed her camera at the moon and fixed it. The animation of the celestial body was thus provided by the rolling ship and the movement of the rough sea. It is therefore not the motif that moves, but the camera itself.

In Baranowsky’s work, the romantic gravitas of the moon, which has inspired artworks of desire such as the figures in paintings by Caspar David Friedrich or the Blue Moon that Elvis Presley sang to so imploringly, has been lost. Instead, the earth’s satellite hops about with an irregular rhythm, wobbling in the predefined playing field of the projected pictorial surface, and is thus hardly suitable any longer as the subject of romantic observations. Viewers are instead cast back upon themselves and their own subjective perspectives, and are led to ask “What really moves the moon?”

The work deals less with gravitas than with gravitation. The artist has created a small conceptual loop. The moon is not entirely innocent when it comes to the ship’s movements. While the waves that cause the camera’s peculiar swaying movements are primarily caused by the wind, they are also influenced by the tides, which, in turn, are influenced by the moon’s own gravitational force. Thus, everything comes full circle: the moon moves the ship, the camera, and, ultimately, itself in the projection.

This recognition is sobering and cannot really explain the attractiveness of the video images. In their formal reduction, many of Baranowsky’s videos seem hermetic, cool, and emotionless. The often fairly short film sequences with their characteristically dispassionate look show everyday motifs that the artist has arranged into loops. Baranowsky succeeded in not freezing the captured movement, and through the careful montaging of images running forwards or in reverse, she was able to expand it into eternity by means of constant repetitions that bring to mind the Greek hero Sisyphus. The documentary austerity of Baranowsky’s images contrasts with the inherent geometry of the repetitions, and thus deals with the ever-so-deceptive difference between reality and nature, its technical and artistic illustration in the video, and our own perception of things, judged by our experience to be normal and correct.

Temporal rhythms usually serve as the starting point in the process, and Baranowsky assembles these into consistently new, complex, and surprising figures, as in her video triptych Radfahrer (Hase und Igel) (Biker [The Hare and the Hedgehog]; 2000). On three projection surfaces arranged next to each other, the work depicts two identical-looking bikers riding in circles on a racecourse. The exact same sequence is shown at different speeds: in real time on the right, slowed down by ten percent in the middle, and slowed down by twenty percent on the left. As a total image, it is almost impossible to recognize that the videos are being played back at different speeds. Instead, the illusion of an impossible continuum is created, as if the bikers were able to ride from one projection into the next, and even to overtake themselves.

In reality, however, the race only takes place in the eye of the viewer, who assembles the fragments. It is no accident that the title already references the well-known fairy tale in which the arrogant hare falls for the trick of the two identical hedgehogs. Caught up in the futile loop of an unending competition, the hare becomes the victim of his superficial perception. The old, handed-down tale was published in 1840 by the dialect poet Wilhelm Schröder with these introductory words: “This story is told fraudulently, boys, but it is nevertheless true, because my grandfather, from whom I heard it, was in the custom of saying when he told it: ‘It has to be true, my boy, otherwise one would not be able to tell it.’”

Baranowsky is less concerned with pillorying the difference between true and false or even with making a moral judgment. Rather, she challenges the eye’s capacity to recognize the fantastic and the implausible in the realistic imagination. To do so, she makes use of tempting everyday motifs, such as the moon, bikers, or a female swimmer in a swimming pool. But the swimmer never takes a breath and never arrives at the edge of the pool, the bikers seem to overcome the dimensions of time and space, and the moon defies the cosmic order of things.

The viewer is led astray, and abysses open up with the doubt of one’s own perception. It is suitable that the title of the piece, Mondfahrt (Lunar Journey), also evokes the brief history of the moon landing and the associated conspiracy theories claiming that the manned voyage to the moon never occurred, but only took place as a filmed event in a Hollywood studio. Baranowsky is more sophisticated and precise in her work; she limits herself to simple, almost schematic processes and ties the ends together. The implausible occurs in the repetition, and over and over again at that. The system comprising the hypnotic repetition of the same thing in geometric variations of digital patterns is exemplary. With it, the artist causes potential interpretations to careen in a purely formalistic play of refractions, reflections, and reversals, like the moon in its capricious and lonely orbit—and, in its retinue, the viewer, too.

Angela Rosenberg

Baranowsky Heike 4151 4065 4051 4049 4059 11381HEIKE BARANOWSKY, MONDFAHRT, 2001

HEIKE BARANOWSKY, SCHWIMMERIN, 2000

HEIKE BARANOWSKY, SCHWIMMERIN, 2000

HEIKE BARANOWSKY, SCHWIMMERIN, 2000

HEIKE BARANOWSKY, SCHWIMMERIN, 2000

Schwimmerin © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2021. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Barbara Weiss, Berlin. © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2021. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Barbara Weiss, Berlin. 2000 Baranowsky Heike 4151 4065 4051 4049 4059 11381HEIKE BARANOWSKY, SCHWIMMERIN, 2000

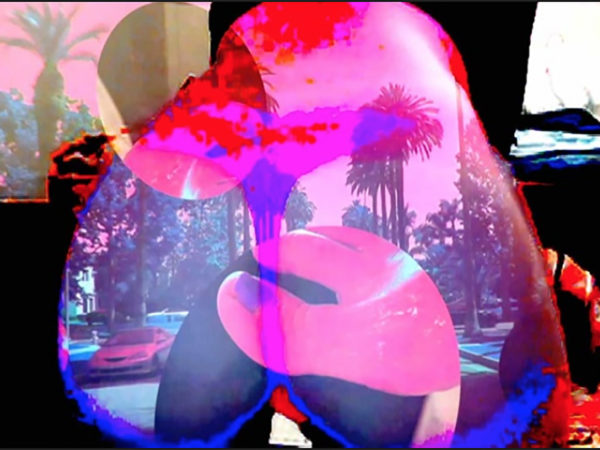

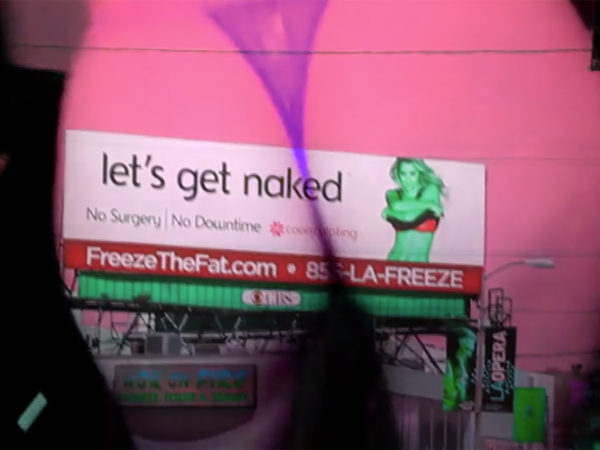

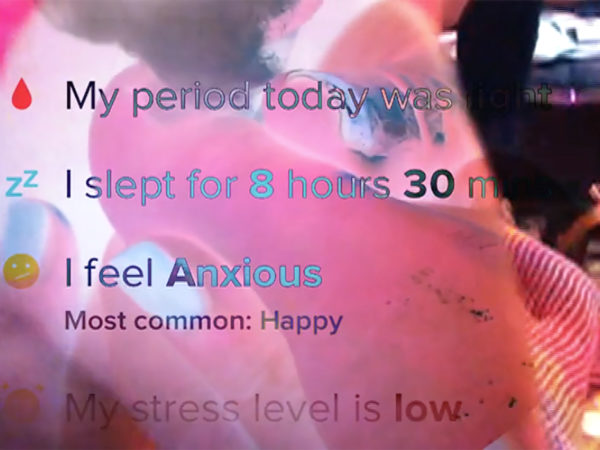

HELEN BENIGSON, A RUDE GIRL ARSE GLISTENS LIKE SILICONE. CLUCK, CLUCK, CLUCK 1, 2015

HELEN BENIGSON, A RUDE GIRL ARSE GLISTENS LIKE SILICONE. CLUCK, CLUCK, CLUCK 1, 2015

HELEN BENIGSON, A RUDE GIRL ARSE GLISTENS LIKE SILICONE. CLUCK, CLUCK, CLUCK 1, 2015

HELEN BENIGSON, A RUDE GIRL ARSE GLISTENS LIKE SILICONE. CLUCK, CLUCK, CLUCK 1, 2015

A Rude Girl Arse Glistens Like Silicone. Cluck, Cluck, Cluck 1 Courtesy of the artist and Daata, London. Courtesy of the artist and Daata, London. 2015A Rude Girl Arse Glistens Like Silicone. Cluck, Cluck, Cluck 1–6 (2015) von Helen Benigson besteht aus einer Reihe von sechs kurzen Videos, die sich um das Thema Junggesell*innenabschied drehen. Darin ist ein pulsierender Körper, der auf eine flache und mit einem Fotofilter bearbeitete Stadtlandschaft collagiert wurde, zu sehen. Der Soundtrack besteht aus digital manipulierten Stimmen, die von einer Junggesell*innenparty inklusive Besäufnis, Gegacker und Online-Postings berichten.

A Rude Girl Arse Glistens Like Silicone. Cluck, Cluck, Cluck 1–6 (2015), by Helen Benigson is a series of six short videos based around the idea of the hen party bachelorette. The beating body is collaged on top of flat, photo filtered cityscapes. The soundtrack is compiled of digitally manipulated voices narrating a hen party experience, pissed, clucking, uploading.

Benigson Helen 4155 4066 4051 4059 12509 11381HELEN BENIGSON, A RUDE GIRL ARSE GLISTENS LIKE SILICONE. CLUCK, CLUCK, CLUCK 1, 2015

HELEN BENIGSON, A RUDE GIRL ARSE GLISTENS LIKE SILICONE. CLUCK, CLUCK, CLUCK 2, 2015

HELEN BENIGSON, A RUDE GIRL ARSE GLISTENS LIKE SILICONE. CLUCK, CLUCK, CLUCK 2, 2015

HELEN BENIGSON, A RUDE GIRL ARSE GLISTENS LIKE SILICONE. CLUCK, CLUCK, CLUCK 2, 2015

HELEN BENIGSON, A RUDE GIRL ARSE GLISTENS LIKE SILICONE. CLUCK, CLUCK, CLUCK 2, 2015

A Rude Girl Arse Glistens Like Silicone. Cluck, Cluck, Cluck 2 Courtesy of the artist and Daata, London. Courtesy of the artist and Daata, London. 2015A Rude Girl Arse Glistens Like Silicone. Cluck, Cluck, Cluck 1–6 (2015) von Helen Benigson besteht aus einer Reihe von sechs kurzen Videos, die sich um das Thema Junggesell*innenabschied drehen. Darin ist ein pulsierender Körper, der auf eine flache und mit einem Fotofilter bearbeitete Stadtlandschaft collagiert wurde, zu sehen. Der Soundtrack besteht aus digital manipulierten Stimmen, die von einer Junggesell*innenparty inklusive Besäufnis, Gegacker und Online-Postings berichten.

A Rude Girl Arse Glistens Like Silicone. Cluck, Cluck, Cluck 1–6 (2015), by Helen Benigson is a series of six short videos based around the idea of the hen party bachelorette. The beating body is collaged on top of flat, photo filtered cityscapes. The soundtrack is compiled of digitally manipulated voices narrating a hen party experience, pissed, clucking, uploading.

Benigson Helen 4155 4066 4051 4059 12509 11381HELEN BENIGSON, A RUDE GIRL ARSE GLISTENS LIKE SILICONE. CLUCK, CLUCK, CLUCK 2, 2015

HELEN BENIGSON, A RUDE GIRL ARSE GLISTENS LIKE SILICONE. CLUCK, CLUCK, CLUCK 3, 2015

HELEN BENIGSON, A RUDE GIRL ARSE GLISTENS LIKE SILICONE. CLUCK, CLUCK, CLUCK 3, 2015

HELEN BENIGSON, A RUDE GIRL ARSE GLISTENS LIKE SILICONE. CLUCK, CLUCK, CLUCK 3, 2015

HELEN BENIGSON, A RUDE GIRL ARSE GLISTENS LIKE SILICONE. CLUCK, CLUCK, CLUCK 3, 2015

A Rude Girl Arse Glistens Like Silicone. Cluck, Cluck, Cluck 3 Courtesy of the artist and Daata, London. Courtesy of the artist and Daata, London. 2015A Rude Girl Arse Glistens Like Silicone. Cluck, Cluck, Cluck 1–6 (2015), by Helen Benigson is a series of six short videos based around the idea of the hen party bachelorette. The beating body is collaged on top of flat, photo filtered cityscapes. The soundtrack is compiled of digitally manipulated voices narrating a hen party experience, pissed, clucking, uploading.

A Rude Girl Arse Glistens Like Silicone. Cluck, Cluck, Cluck 1–6 (2015) von Helen Benigson besteht aus einer Reihe von sechs kurzen Videos, die sich um das Thema Junggesell*innenabschied drehen. Darin ist ein pulsierender Körper, der auf eine flache und mit einem Fotofilter bearbeitete Stadtlandschaft collagiert wurde, zu sehen. Der Soundtrack besteht aus digital manipulierten Stimmen, die von einer Junggesell*innenparty inklusive Besäufnis, Gegacker und Online-Postings berichten.

Benigson Helen 4155 4066 4051 4059 12509 11381HELEN BENIGSON, A RUDE GIRL ARSE GLISTENS LIKE SILICONE. CLUCK, CLUCK, CLUCK 3, 2015

HELEN BENIGSON, A RUDE GIRL ARSE GLISTENS LIKE SILICONE. CLUCK, CLUCK, CLUCK 4, 2015

HELEN BENIGSON, A RUDE GIRL ARSE GLISTENS LIKE SILICONE. CLUCK, CLUCK, CLUCK 4, 2015

HELEN BENIGSON, A RUDE GIRL ARSE GLISTENS LIKE SILICONE. CLUCK, CLUCK, CLUCK 4, 2015

HELEN BENIGSON, A RUDE GIRL ARSE GLISTENS LIKE SILICONE. CLUCK, CLUCK, CLUCK 4, 2015

A Rude Girl Arse Glistens Like Silicone. Cluck, Cluck, Cluck 4 Courtesy of the artist and Daata, London. Courtesy of the artist and Daata, London. 2015A Rude Girl Arse Glistens Like Silicone. Cluck, Cluck, Cluck 1–6 (2015) von Helen Benigson besteht aus einer Reihe von sechs kurzen Videos, die sich um das Thema Junggesell*innenabschied drehen. Darin ist ein pulsierender Körper, der auf eine flache und mit einem Fotofilter bearbeitete Stadtlandschaft collagiert wurde, zu sehen. Der Soundtrack besteht aus digital manipulierten Stimmen, die von einer Junggesell*innenparty inklusive Besäufnis, Gegacker und Online-Postings berichten.

A Rude Girl Arse Glistens Like Silicone. Cluck, Cluck, Cluck 1–6 (2015), by Helen Benigson is a series of six short videos based around the idea of the hen party bachelorette. The beating body is collaged on top of flat, photo filtered cityscapes. The soundtrack is compiled of digitally manipulated voices narrating a hen party experience, pissed, clucking, uploading.

Benigson Helen 4155 4066 4051 4059 12509 11381HELEN BENIGSON, A RUDE GIRL ARSE GLISTENS LIKE SILICONE. CLUCK, CLUCK, CLUCK 4, 2015

HELEN BENIGSON, A RUDE GIRL ARSE GLISTENS LIKE SILICONE. CLUCK, CLUCK, CLUCK 5, 2015

HELEN BENIGSON, A RUDE GIRL ARSE GLISTENS LIKE SILICONE. CLUCK, CLUCK, CLUCK 5, 2015

HELEN BENIGSON, A RUDE GIRL ARSE GLISTENS LIKE SILICONE. CLUCK, CLUCK, CLUCK 5, 2015

HELEN BENIGSON, A RUDE GIRL ARSE GLISTENS LIKE SILICONE. CLUCK, CLUCK, CLUCK 5, 2015

A Rude Girl Arse Glistens Like Silicone. Cluck, Cluck, Cluck 5 Courtesy of the artist and Daata, London. Courtesy of the artist and Daata, London. 2015A Rude Girl Arse Glistens Like Silicone. Cluck, Cluck, Cluck 1–6 (2015) von Helen Benigson besteht aus einer Reihe von sechs kurzen Videos, die sich um das Thema Junggesell*innenabschied drehen. Darin ist ein pulsierender Körper, der auf eine flache und mit einem Fotofilter bearbeitete Stadtlandschaft collagiert wurde, zu sehen. Der Soundtrack besteht aus digital manipulierten Stimmen, die von einer Junggesell*innenparty inklusive Besäufnis, Gegacker und Online-Postings berichten.

A Rude Girl Arse Glistens Like Silicone. Cluck, Cluck, Cluck 1–6 (2015), by Helen Benigson is a series of six short videos based around the idea of the hen party bachelorette. The beating body is collaged on top of flat, photo filtered cityscapes. The soundtrack is compiled of digitally manipulated voices narrating a hen party experience, pissed, clucking, uploading.

Benigson Helen 4155 4066 4051 4059 12509 11381HELEN BENIGSON, A RUDE GIRL ARSE GLISTENS LIKE SILICONE. CLUCK, CLUCK, CLUCK 5, 2015

HELEN BENIGSON, A RUDE GIRL ARSE GLISTENS LIKE SILICONE. CLUCK, CLUCK, CLUCK 6, 2015

HELEN BENIGSON, A RUDE GIRL ARSE GLISTENS LIKE SILICONE. CLUCK, CLUCK, CLUCK 6, 2015

HELEN BENIGSON, A RUDE GIRL ARSE GLISTENS LIKE SILICONE. CLUCK, CLUCK, CLUCK 6, 2015

HELEN BENIGSON, A RUDE GIRL ARSE GLISTENS LIKE SILICONE. CLUCK, CLUCK, CLUCK 6, 2015

A Rude Girl Arse Glistens Like Silicone. Cluck, Cluck, Cluck 6 Courtesy of the artist and Daata, London. Courtesy of the artist and Daata, London. 2015A Rude Girl Arse Glistens Like Silicone. Cluck, Cluck, Cluck 1–6 (2015) von Helen Benigson besteht aus einer Reihe von sechs kurzen Videos, die sich um das Thema Junggesell*innenabschied drehen. Darin ist ein pulsierender Körper, der auf eine flache und mit einem Fotofilter bearbeitete Stadtlandschaft collagiert wurde, zu sehen. Der Soundtrack besteht aus digital manipulierten Stimmen, die von einer Junggesell*innenparty inklusive Besäufnis, Gegacker und Online-Postings berichten.

A Rude Girl Arse Glistens Like Silicone. Cluck, Cluck, Cluck 1–6 (2015), by Helen Benigson is a series of six short videos based around the idea of the hen party bachelorette. The beating body is collaged on top of flat, photo filtered cityscapes. The soundtrack is compiled of digitally manipulated voices narrating a hen party experience, pissed, clucking, uploading.

Benigson Helen 4155 4066 4051 4059 12509 11381HELEN BENIGSON, A RUDE GIRL ARSE GLISTENS LIKE SILICONE. CLUCK, CLUCK, CLUCK 6, 2015

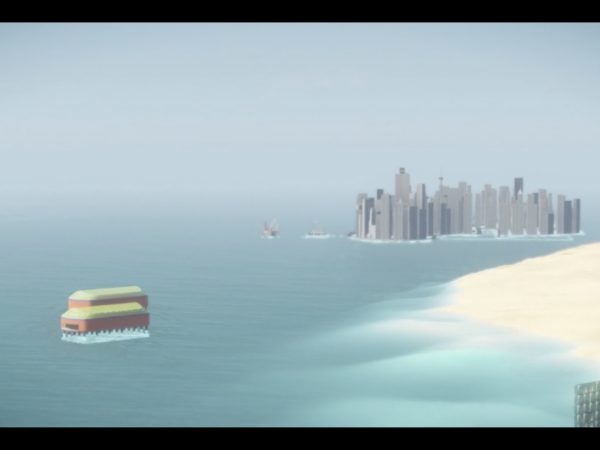

MERIEN BENNANI, PARTY ON THE CAPS, 2018

MERIEN BENNANI, PARTY ON THE CAPS, 2018

MERIEN BENNANI, PARTY ON THE CAPS, 2018

MERIEN BENNANI, PARTY ON THE CAPS, 2018

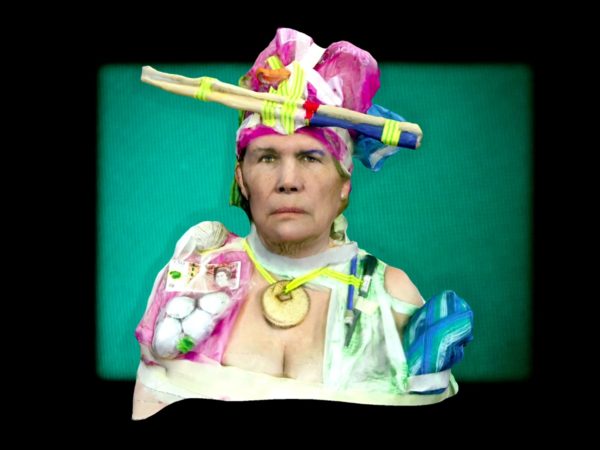

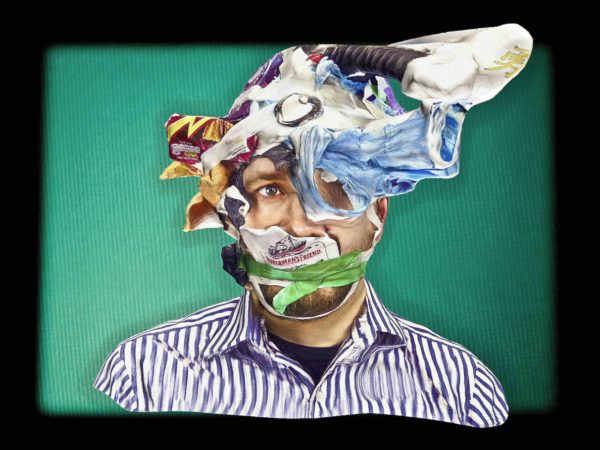

Party on the CAPS Videostill. Courtesy of the artist, BIM 2018 and C L E A R I N G, New York/Brussels. Video still. Courtesy of the artist, BIM 2018 and C L E A R I N G, New York/Brussels. 2018Party on the CAPS ist ein fiktiver Dokumentarfilm in einer spekulativen Zukunft über den Alltag auf CAPS, einer Insel mitten im Atlantik, auf der Migranten festgehalten werden, und die sich im Laufe der Zeit zu einer Megacity entwickelt hat. Der scheinbare Realismus wird übersteigert durch Spezialeffekte und Humor. Bennanis ungewöhnliche Bildsprache mischt Einflüsse von Reality-TV, YouTube, Dokumentarfilm, Social Media und Animation und erkundet so die Grenzen dessen, was wir als vertraut und seltsam, real und virtuell betrachten.

In der zukünftigen Welt, in der die Insel CAPS (Kurzform von „capsule“, deutsch: Kapsel) existiert, hat die Teleportation andere Formen des Reisens ersetzt, sodass Körper physische und nationale Grenzen leicht überqueren können. CAPS wurde als temporärer Aufenthaltsort für illegale Migrant*innen eingerichtet, die während der Teleportation in die USA abgefangen wurden. Die Insel ist von einem Magnetfeld umgeben, wird von US-Truppen kontrolliert und unterliegt einer totalen Überwachung, die es beinahe unmöglich macht, sie zu verlassen. Bennanis Doku-Story beginnt zwei Generationen nach der Einrichtung von CAPS: Abgeschnitten vom Rest der Welt, haben sich eine eigene Logik, Währung, Infrastruktur, Küche sowie eigene Medien entwickelt. CAPS ist ein Ort kultureller Hybridität, die in den unzähligen Identitäten der Bevölkerung, ihrer behelfsmäßigen Lebenssituation und der Dominanz digitaler Technologien gründet. Die Insel wird von cyborgartigen, oft verletzten Körpern bewohnt, die sich an die repressive Umgebung der Insel und die Folgen der Teleportation anpassen und damit umgehen lernen.

Die Idee für CAPS hatte die in New York lebende und arbeitende marokkanische Künstlerin im Jahr 2017, als sie sich mit subatomarer Teleportation beschäftigte und Donald Trump ein US-Einreiseverbot für Menschen aus einigen mehrheitlich muslimischen Ländern verhängte. Party on the CAPS leistet einen scharfsinnigen politischen Kommentar zur westlichen Einwanderungs- und Überwachungspolitik und ruft eine dystopische Welt hervor, die sich kaum mehr von unserer unterscheidet. In ihrer Arbeit würdigt Bennani aber auch die psychische Widerstandsfähigkeit (Resilienz), Differenz und Hybridität vertriebener und in der Diaspora lebender Menschen, indem sie sich essentialistischen Vorstellungen von Identität und Kultur widersetzt. Als Zuschauer*innen werden wir Zeug*innen einer Feier – oder Party – von Gemeinschaftlichkeit und Familie.

Lisa Long

Conceived as a documentary set in a speculative future about daily life on CAPS, an island turned megacity in the middle of the Atlantic, where migrants are detained, the work amplifies reality through special effects and humor. Party on the CAPS highlights Bennani’s playful and unique visual language inspired by reality TV, YouTube, documentary, social media, and animation, examining the boundaries of what we regard as familiar and strange, real and virtual.

In the future world in which the island of CAPS (short for capsule) exists, teleportation has replaced other forms of travel, enabling bodies to easily move from one place to another. CAPS was established as a temporary holding area for illegal migrants intercepted mid-teleportation on their way to the US. The island is surrounded by a magnetic field, guarded by US troops, and subject to total surveillance, making it almost impossible to leave. Bennani’s docunarrative begins two generations after the establishment of CAPS: cut off from the rest of the world, the island has developed its own internal logic, currency, infrastructure, traditions, cuisine, and media. CAPS is characterized by a mélange of hybrid cultures—growing out of the myriad identities of its inhabitants, their makeshift living situation, and the dominance of digital technologies—and is populated by cyborgian, often injured, bodies adapting to and coping with the island’s oppressive environment and the aftereffects of teleportation.

Bennani, a Moroccan artist based in New York, conceptualized CAPS in 2017 while researching subatomic teleportation and in response to Donald Trump’s US travel ban. The work offers an acute political commentary on Western immigration and surveillance policies, summoning a dystopian reality only slightly different from our own. In the work, Bennani also pays tribute to human resilience, to difference, and hybridity by resisting essentialist notions of identity and culture, instead addressing the in-between and multiple states of life in the diaspora. As viewers we are witness to a celebration—or party—of collectivity and family.

Lisa Long

Bennani Meriem 13580 4059 4051 4066MERIEN BENNANI, PARTY ON THE CAPS, 2018

JOHANNA BILLING, PROJECT FOR A REVOLUTION, 2000

JOHANNA BILLING, PROJECT FOR A REVOLUTION, 2000

JOHANNA BILLING, PROJECT FOR A REVOLUTION, 2000

JOHANNA BILLING, PROJECT FOR A REVOLUTION, 2000

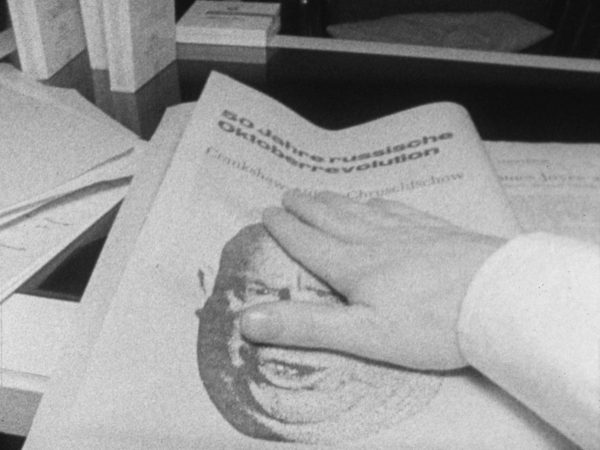

Project for a Revolution A film by Johanna Billing. Cinematography by Johan Phillips & Henry Moore Selder. Sound by Mario Adamsson. Co-produced by Riksutställningar. © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2021. Courtesy of the artist and Kavi Gupta, Chicago. A film by Johanna Billing. Cinematography by Johan Phillips & Henry Moore Selder. Sound by Mario Adamsson. Co-produced by Riksutställningar. © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2021. Courtesy of the artist and Kavi Gupta, Chicago. 2000Der Film Zabriskie Point (1970) von Michelangelo Antonioni spielt Ende der 1960er-Jahre in Los Angeles während der amerikanischen Studenten- und Bürgerrechtsbewegung. In der Eröffnungssequenz diskutieren radikale Studenten über ihre Strategie zur Ausrichtung eines Aufstandes gegen das Establishment. Der Saal ist überfüllt, alle reden durcheinander, es gibt Gelächter, Einwände, einen hitzigen Schlagabtausch. Der Protagonist Mark steht plötzlich auf und verkündet provokativ: „Auch ich bin bereit zu sterben. […] Aber nicht aus Langeweile“1und verlässt den Raum.2

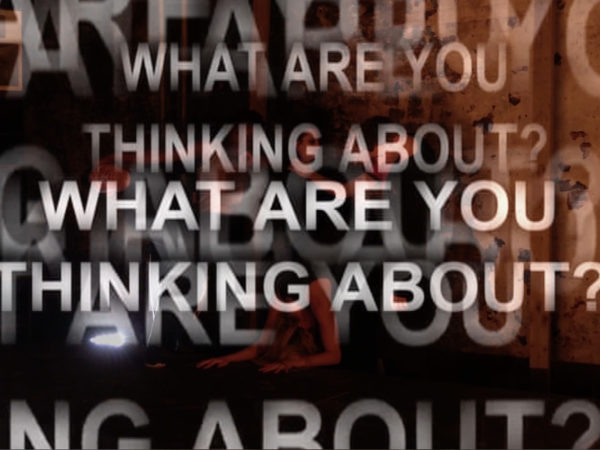

Von der aufgeheizten Stimmung des bevorstehenden Studentenprotests ist bei Johanna Billings Project for a Revolution (2000) nichts mehr zu spüren. Die Videoarbeit beginnt mit der Nahaufnahme eines Fotokopierers, der statt politischer Pamphlete lediglich leere Blätter ausgibt. In einem nüchternen Zimmer hat sich eine Gruppe junger Menschen versammelt. Wie in der Anfangsszene von Zabriskie Point fokussiert die Kamera einzelne Gesichter in Vollbildgroßaufnahme. Die jungen Erwachsenen sitzen gelangweilt auf ihren Stühlen, trinken Kaffee aus Plastikbechern, kauen an ihren Fingernägeln oder lesen in einem Buch. Es gibt weder Blickkontakte noch Gespräche. Das Fehlen jeglicher Interaktion evoziert eine Situation des Wartens, die durch die Abwesenheit von Musik – es ertönen lediglich Umgebungsgeräusche – zusammen mit der langsamen Abfolge der Nahaufnahmen betont wird. Unterbrochen wird die kontemplative Monotonie durch Sequenzen mit langen Kameraeinstellungen, die einen jungen Mann zeigen, der sich – konträr zu der Gruppe – in ständiger Bewegung befindet. Er läuft verschiedene Treppenhäuser hinunter und hinauf, bis er schließlich den Raum mit den Wartenden betritt. Er zögert kurz, bevor er auf einen Stuhl zustürmt, von dem er eines der leeren Flugblätter ergreift und sich wieder in Richtung Ausgang bewegt. Ähnlich wie Mark in Zabriskie Point tritt er zwar als aktiver Individualist auf, hat aber letztendlich kein klares Ziel vor Augen. Denn die Videoarbeit ist geloopt, sodass sich die Narration im Kreis dreht.

Billing versetzt ihre Reminiszenz an Zabriskie Point ins Jahr 2000 und in ihre Heimatstadt Stockholm. Die Künstlerin beschreibt die Situation ihrer Generation folgendermaßen: „Es war die Generation unserer Eltern, die den Aufstand probte. Sie hat uns den Weg geebnet, und man sagte uns, alles sei nun erledigt und wir müssten uns keine Gedanken mehr machen. Wir sollten unserer Karriere nachgehen und in unser eigenes Leben investieren.“3 Damals waren die jungen Menschen in einem ideologischen Vakuum gefangen. Sie befanden sich zeitlich gesehen zwischen dem vom Politikwissenschaftler Francis Fukuyama titulierten, vermeintlichen „Ende der Geschichte“4 , das durch den Niedergang des Ostblocks gekennzeichnet ist und als Folge die globale Durchsetzung der Demokratie und Marktwirtschaft prognostiziert, und vor dessen Revidierung durch die Terroranschläge am 11. September 2001. Die Gesellschaft ist durch den Individualismus geprägt, in dem jeder sein Privatleben selbstbestimmt verwirklichen kann. So entsteht ein Tauziehen zwischen Individualität und Kollektivität. Die Einzelnen haben sich nichts mehr zu sagen, sie haben kein gemeinsames Ziel, kein kollektives Feindbild, für das es sich zu kämpfen lohnt. Trotzdem blicken sie verklärt auf das große Vorbild der 1968er-Generation zurück. Sie verspüren das Bedürfnis, aus dem Schatten ihrer Eltern herauszutreten. Doch wofür lohnt es sich einzutreten, wenn bereits alle Freiheiten zur Verfügung stehen? Das „Projekt für eine Revolution“, wie der Titel der Arbeit suggeriert, verharrt letztendlich in einer sich im Leerlauf befindenden Lethargie, die durch den Loop des narrativen Handlungsstrangs ins Endlose repetiert wird.

Anna-Alexandra Pfau

1 Michelangelo Antonioni: Zabriskie Point, Frankfurt am Main 1985, S. 13 f.

2 Vgl. Claudia Lenssen: „Filmographie“, in: Michelangelo Antonini, Reihe Film 31, München und Wien 1984, S. 181–192.

3 Johanna Billing, in: Äsa Nacking: The collective as an option. An interview with Johanna Billing for Rooseum Provisorim, 2001, http://www.makeithappen.org/jbaninterview.html, Stand: 16.12.2011.

4 Vgl. Francis Fukuyama: Das Ende der Geschichte. Wo stehen wir?, München 1992.

The film Zabriskie Point (1970) by Michelangelo Antonioni plays in Los Angeles during the days of the American student and civil rights movement in the late 1960s. In the opening sequence, radical students are seen discussing their strategy for an anti-establishment protest. The room is full to overflowing, everyone is talking at once; we can hear laughter, objections, a heated debate. Suddenly, protagonist Mark gets up and declares provocatively: “I am also prepared to die … But not of boredom.”1 He leaves the room.2

In Johanna Billing’s Project for a Revolution (2000) there is no trace left of the heated mood of the imminent student protest. The video begins with a close-up of a photocopier, which rather than ejecting political pamphlets only spits out empty sheets of paper. In a sparsely furnished room, a group of young people has gathered. As in the opening scene of Zabriskie Point, the camera focuses on individual faces in a large format close-up. The young adults sit around languidly on their chairs, drink coffee from plastic beakers, chew their fingernails or read. They neither exchange glances nor do they speak. This lack of any interaction evokes a situation of waiting, which is heightened by the absence of music (we hear only ambient sounds) and the slow succession of close-ups. The contemplative monotony is interrupted by sequences with long camera shots depicting a young man, who unlike the people in the group is in constant motion. He runs up and down different flights of stairs until he finally enters the room of waiting persons. He pauses briefly before rushing up to a chair from which he grabs one of the empty pamphlets and then makes for the exit again. Similarly to Mark in Zabriskie Point, he features as an active individualist but ultimately he does not have a clear goal. The reason: the video piece is looped so that the narration goes round in a circle.

Billing transfers her memories of Zabriskie Point into the year 2000 and to her native city of Stockholm. The artist describes the situation of her generation as follows: “It was our parents’ generation who brought the revolution. They took care of all that for us and we were told that now everything had been done and it wasn’t something we need be bothered with. We were to pursue a career and invest in our own lives.”3 Back then, young people found themselves caught in an ideological vacuum. Chronologically speaking, they found themselves between what political scientist Francis Fukuyama claimed was the “end of history,”4 a state characterized by the demise of the Eastern block and consequently the global assertion of democracy and market economy, and the period prior to its revision by the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. Society is characterized by individualism allowing everyone to realize their private lives as they see fit. This produces a tug-of-war between individuality and collectivity. Individuals no longer have anything to say to one another, they do not have a joint goal, nor do they possess a collective concept of an enemy it would be worth fighting. Nonetheless, they look back in an idealized manner at the great model of the generation from the days of the student movement. They sense the need to emerge from the shadows of their parents. But what is it worth standing up for when they already have all the liberties they want? As the title suggests, Project for a Revolution ultimately remains in an idling lethargy, which is repeated interminably through the loop of the narrative strand.

Anna-Alexandra Pfau

1 Michelangelo Antonioni, Zabriskie Point (Frankfurt/ Main, 1985), p. 13f.

2 See Claudia Lenssen, “Filmographie,” in Michelangelo Antonini, series film 31 (Munich and Vienna, 1984), pp. 181–192.

3 Johanna Billing, in Äsa Nacking, The collective as an option: An interview with Johanna Billing for Rooseum Provisorim (2001), http://www.makeithappen.org/jbaninterview.html, accessed December 16, 2011.

4 See Francis Fukuyama, The End of History (Munich, 1992).

Billing Johanna 4160 4065 4051 4059 11381JOHANNA BILLING, PROJECT FOR A REVOLUTION, 2000

DAVID BLANDY, ICE, 2015

DAVID BLANDY, ICE, 2015

DAVID BLANDY, ICE, 2015

DAVID BLANDY, ICE, 2015

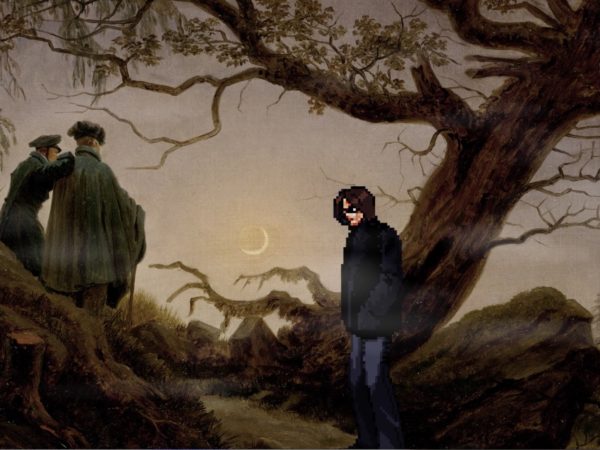

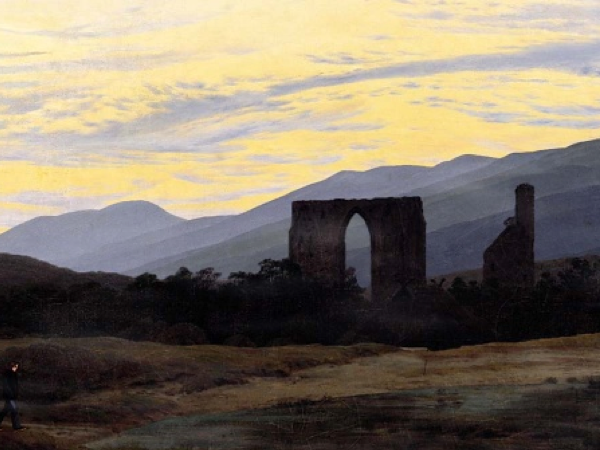

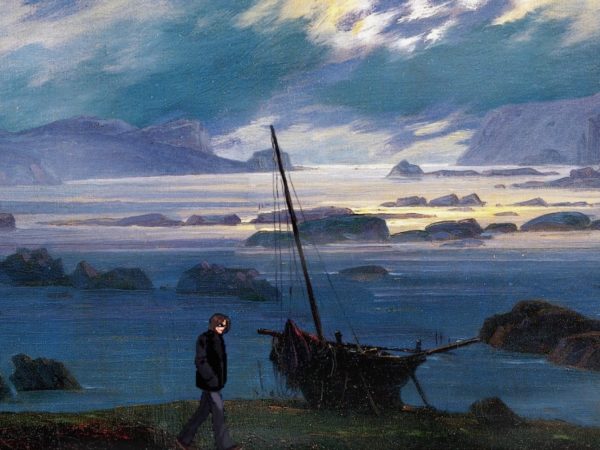

Ice Courtesy of the artist and Daata, London. Courtesy of the artist and Daata, London. 2015In jedem der sechs Videos von Blandy wandelt eine verpixelte Version des Künstlers – sie scheint wie aus einem alten Computerspiel entsprungen – durch Landschaften, bei denen es sich um Adaptionen und Kombinationen von Darstellungen aus Gemälden Caspar David Friedrichs handelt, dem berühmtesten Maler der deutschen Romantik im 19. Jahrhundert.

Throughout each of Blandy’s 6 videos, a pixelated version of the artist, as though exited from an old computer game, walks through landscapes which are adaptations and combinations of paintings by the 19th-century German Romantic landscape painter, Caspar David Friedrich.

Blandy David 4164 4066 4051 4059 12509 11381DAVID BLANDY, ICE, 2015

DAVID BLANDY, MIST, 2015

DAVID BLANDY, MIST, 2015

DAVID BLANDY, MIST, 2015

DAVID BLANDY, MIST, 2015

Mist Courtesy of the artist and Daata, London. Courtesy of the artist and Daata, London. 2015In jedem der sechs Videos von Blandy wandelt eine verpixelte Version des Künstlers – sie scheint wie aus einem alten Computerspiel entsprungen – durch Landschaften, bei denen es sich um Adaptionen und Kombinationen von Darstellungen aus Gemälden Caspar David Friedrichs handelt, dem berühmtesten Maler der deutschen Romantik im 19. Jahrhundert.

Throughout each of Blandy’s 6 videos, a pixelated version of the artist, as though exited from an old computer game, walks through landscapes which are adaptations and combinations of paintings by the 19th-century German Romantic landscape painter, Caspar David Friedrich.

Blandy David 4164 4066 4051 4059 12509 11381DAVID BLANDY, MIST, 2015

DAVID BLANDY, MOON, 2015

DAVID BLANDY, MOON, 2015

DAVID BLANDY, MOON, 2015

DAVID BLANDY, MOON, 2015

Moon Courtesy of the artist and Daata Editions, London. Courtesy of the artist and Daata Editions, London. 2015In jedem der sechs Videos von Blandy wandelt eine verpixelte Version des Künstlers – sie scheint wie aus einem alten Computerspiel entsprungen – durch Landschaften, bei denen es sich um Adaptionen und Kombinationen von Darstellungen aus Gemälden Caspar David Friedrichs handelt, dem berühmtesten Maler der deutschen Romantik im 19. Jahrhundert.

Throughout each of Blandy’s 6 videos, a pixelated version of the artist, as though exited from an old computer game, walks through landscapes which are adaptations and combinations of paintings by the 19th-century German Romantic landscape painter, Caspar David Friedrich.

Blandy David 4164 4066 4051 4059 12509 11381DAVID BLANDY, MOON, 2015

DAVID BLANDY, RUIN, 2015

DAVID BLANDY, RUIN, 2015

DAVID BLANDY, RUIN, 2015

DAVID BLANDY, RUIN, 2015

Ruin Courtesy of the artist and Daata, London. Courtesy of the artist and Daata, London. 2015In jedem der sechs Videos von Blandy wandelt eine verpixelte Version des Künstlers – sie scheint wie aus einem alten Computerspiel entsprungen – durch Landschaften, bei denen es sich um Adaptionen und Kombinationen von Darstellungen aus Gemälden Caspar David Friedrichs handelt, dem berühmtesten Maler der deutschen Romantik im 19. Jahrhundert.

Throughout each of Blandy’s 6 videos, a pixelated version of the artist, as though exited from an old computer game, walks through landscapes which are adaptations and combinations of paintings by the 19th-century German Romantic landscape painter, Caspar David Friedrich.

Blandy David 4164 4066 4051 4059 12509 11381DAVID BLANDY, RUIN, 2015

DAVID BLANDY, SEA, 2015

DAVID BLANDY, SEA, 2015

DAVID BLANDY, SEA, 2015

DAVID BLANDY, SEA, 2015

Sea Courtesy of the artist and Daata, London. Courtesy of the artist and Daata, London. 2015In jedem der sechs Videos von Blandy wandelt eine verpixelte Version des Künstlers – sie scheint wie aus einem alten Computerspiel entsprungen – durch Landschaften, bei denen es sich um Adaptionen und Kombinationen von Darstellungen aus Gemälden Caspar David Friedrichs handelt, dem berühmtesten Maler der deutschen Romantik im 19. Jahrhundert.

Throughout each of Blandy’s 6 videos, a pixelated version of the artist, as though exited from an old computer game, walks through landscapes which are adaptations and combinations of paintings by the 19th-century German Romantic landscape painter, Caspar David Friedrich.

Blandy David 4164 4066 4051 4059 12509 11381DAVID BLANDY, SEA, 2015

DAVID BLANDY, SUNSET, 2015

DAVID BLANDY, SUNSET, 2015

DAVID BLANDY, SUNSET, 2015

DAVID BLANDY, SUNSET, 2015

Sunset Courtesy of the artist and Daata, London. Courtesy of the artist and Daata, London. 2015In jedem der sechs Videos von Blandy wandelt eine verpixelte Version des Künstlers – sie scheint wie aus einem alten Computerspiel entsprungen – durch Landschaften, bei denen es sich um Adaptionen und Kombinationen von Darstellungen aus Gemälden Caspar David Friedrichs handelt, dem berühmtesten Maler der deutschen Romantik im 19. Jahrhundert.

Throughout each of Blandy’s 6 videos, a pixelated version of the artist, as though exited from an old computer game, walks through landscapes which are adaptations and combinations of paintings by the 19th-century German Romantic landscape painter, Caspar David Friedrich.

Blandy David 4164 4066 4051 4059 12509 11381DAVID BLANDY, SUNSET, 2015

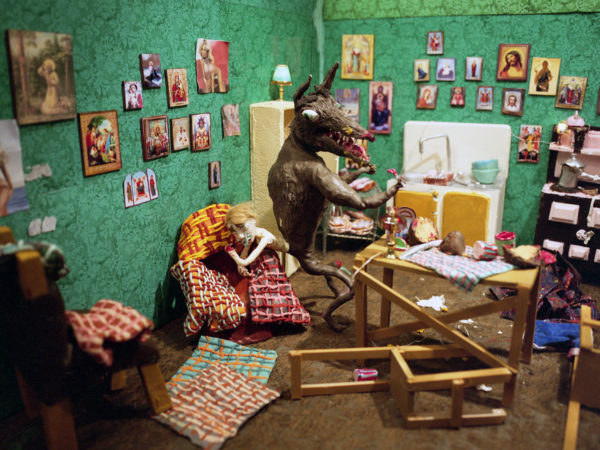

JOHN BOCK, UNHEIL, 2018

JOHN BOCK, UNHEIL, 2018

JOHN BOCK, UNHEIL, 2018

JOHN BOCK, UNHEIL, 2018

Unheil Courtesy of the artist. Courtesy of the artist. 2018 Bock John 4166 4066 4051 4059 11381JOHN BOCK, UNHEIL, 2018

JOHN BOCK, BAUCHHÖHLE BAUCHEN, 2011

JOHN BOCK, BAUCHHÖHLE BAUCHEN, 2011

JOHN BOCK, BAUCHHÖHLE BAUCHEN, 2011

JOHN BOCK, BAUCHHÖHLE BAUCHEN, 2011

Bauchhöhle bauchen Courtesy of the artist. Courtesy of the artist. 2011 Bock John 4166 4066 4051 4059 11381JOHN BOCK, BAUCHHÖHLE BAUCHEN, 2011

JOHN BOCK, LICHTERLOH ROH, 2011

JOHN BOCK, LICHTERLOH ROH, 2011

JOHN BOCK, LICHTERLOH ROH, 2011

JOHN BOCK, LICHTERLOH ROH, 2011

Lichterloh Roh Courtesy of the artist. Courtesy of the artist. 2011 Bock John 4166 4066 4051 4059 11381JOHN BOCK, LICHTERLOH ROH, 2011

JOHN BOCK, MONSIEUR ET MONSIEUR, 2011

JOHN BOCK, MONSIEUR ET MONSIEUR, 2011

JOHN BOCK, MONSIEUR ET MONSIEUR, 2011

JOHN BOCK, MONSIEUR ET MONSIEUR, 2011

Monsieur et Monsieur Courtesy of the artist. Courtesy of the artist. 2011 Bock John 4166 4066 4051 4059 11381JOHN BOCK, MONSIEUR ET MONSIEUR, 2011

JOHN BOCK, NICHTS UNTER DER KINNLADE, 2011

JOHN BOCK, NICHTS UNTER DER KINNLADE, 2011

JOHN BOCK, NICHTS UNTER DER KINNLADE, 2011

JOHN BOCK, NICHTS UNTER DER KINNLADE, 2011

Nichts unter der Kinnlade Courtesy of the artist. Courtesy of the artist. 2011 Bock John 4166 4066 4051 4059 11381JOHN BOCK, NICHTS UNTER DER KINNLADE, 2011

JOHN BOCK, IM SCHATTEN DER MADE, 2010

JOHN BOCK, IM SCHATTEN DER MADE, 2010

JOHN BOCK, IM SCHATTEN DER MADE, 2010

JOHN BOCK, IM SCHATTEN DER MADE, 2010

Im Schatten der Made Courtesy of the artist. Courtesy of the artist. 2010 Bock John 4166 4066 4051 4059 11381JOHN BOCK, IM SCHATTEN DER MADE, 2010

JOHN BOCK, PI-BEAN, 2010

JOHN BOCK, PI-BEAN, 2010

JOHN BOCK, PI-BEAN, 2010

JOHN BOCK, PI-BEAN, 2010

Pi-Bean Courtesy of the artist. Courtesy of the artist. 2010 Bock John 4166 4066 4051 4059 11381JOHN BOCK, PI-BEAN, 2010

JOHN BOCK, SEEWOLF, 2010

JOHN BOCK, SEEWOLF, 2010

JOHN BOCK, SEEWOLF, 2010

JOHN BOCK, SEEWOLF, 2010

Seewolf Courtesy of the artist. Courtesy of the artist. 2010 Bock John 4166 4066 4051 4059 11381JOHN BOCK, SEEWOLF, 2010

JOHN BOCK, DIE ABGESCHMIERTE KNICKLENKUNG IM GEPÄCK VERHEDDERT SICH IM WEISSEN HEMD, 2009

JOHN BOCK, DIE ABGESCHMIERTE KNICKLENKUNG IM GEPÄCK VERHEDDERT SICH IM WEISSEN HEMD, 2009

JOHN BOCK, DIE ABGESCHMIERTE KNICKLENKUNG IM GEPÄCK VERHEDDERT SICH IM WEISSEN HEMD, 2009

JOHN BOCK, DIE ABGESCHMIERTE KNICKLENKUNG IM GEPÄCK VERHEDDERT SICH IM WEISSEN HEMD, 2009

Die abgeschmierte Knicklenkung im Gepäck verheddert sich im weißen Hemd Courtesy of the artist. Courtesy of the artist. 2009 Bock John 4166 4065 4051 4059 11381JOHN BOCK, DIE ABGESCHMIERTE KNICKLENKUNG IM GEPÄCK VERHEDDERT SICH IM WEISSEN HEMD, 2009

JOHN BOCK, LÜTTE MIT RUCOLA, 2006

JOHN BOCK, LÜTTE MIT RUCOLA, 2006

JOHN BOCK, LÜTTE MIT RUCOLA, 2006

JOHN BOCK, LÜTTE MIT RUCOLA, 2006

Lütte mit Rucola Courtesy of the artist. Courtesy of the artist. 2006Der Film Lütte mit Rucola (2006) handelt von einem psychotisch gestörten Mann, dargestellt vom Künstler, der mit einem im Hausflur spielenden und Voodoo-Zauber praktizierenden Mädchen namens Lütte telepathisch kommuniziert. Von ihr ferngelenkt begeht er in seiner Wohnung blutrünstige Morde, foltert und zerstückelt seine Opfer während grausamer Experimente, die er auf der Suche nach existenzieller Orientierung analytisch deutet.

Benny Höhne

The film Lütte mit Rucola (2006) is about a mentally disturbed man, played by the artist, who telepathically communicates with a girl named Lütte who plays in the hallway of the house and practices voodoo magic. Guided by her from afar, he commits bloody murders in his apartment, torturing and cutting up his victims in gruesome experiments, which he interprets analytically on his search for existential orientation.

Benny Höhne

Bock John 4166 4065 4051 4059 11381JOHN BOCK, LÜTTE MIT RUCOLA, 2006

JOHN BOCK, ZEZZIMINNEGESANG, 2006

JOHN BOCK, ZEZZIMINNEGESANG, 2006

JOHN BOCK, ZEZZIMINNEGESANG, 2006

JOHN BOCK, ZEZZIMINNEGESANG, 2006

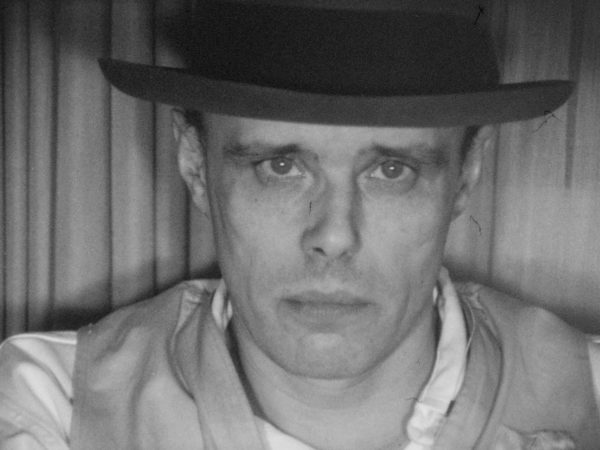

Zezziminnegesang Courtesy of the artist. Courtesy of the artist. 2006Zu Beginn ist alles schwarz. Ein Streichholz flammt auf: man sieht das angespannte, unrasierte Gesicht des Künstlers, der sich eine Zigarette anzündet. Schon ist es wieder dunkel, nur die Glut ist sichtbar, die mit seinen Zügen aufleuchtet. Dann schaltet der Künstler das Licht an, schlägt ein Ei auf, reibt sich die Hüfte mit Eiweiß ein, hält einen Augenblick inne, steigt mühsam von seinem Lager, setzt sich eine Mütze auf, wickelt sich in seinen Bademantel. Als er sich auf eine alte Couch setzt und anfängt, Knöpfe auf ein Kissen zu nähen, sitzt dort bereits eine unheimliche Gestalt mit schwarz geschminktem Gesicht, schwarzer Lockenperücke und Pailletten-Gewand, dargestellt von dem Künstler Adrian Lohmüller. Im Spiegel aber, der vor der Couch steht, ist nur der Künstler-Eremit zu sehen – er springt auf. […]

Im Zezziminnegesang bleibt John Bock fast stumm – er agiert, erklärt sich aber weder den Betrachter*innen noch den anderen Figuren im Video. Mit Hammer und Meißel macht er sich nicht an einem Stein zu schaffen, sondern an einer Dose Ravioli, bis er sie brachial geöffnet hat. Das Essen gestaltet sich schwierig, denn der Löffel ist an einem großen Wohnzimmersessel befestigt, und um das Essen zum Mund zu führen, muss der Sessel über der Schulter in die Luft gestemmt werden. Nach zwei Löffeln ist Schluss, noch ein Schluck Wasser aus dem Gestänge eines Stahlrohrhockers, und dann leckt der Künstler-Eremit einen leeren Küchenschrank aus, der wohl einzige leere Schrank in der Wohnung. Denn sonst ist alles vollgestopft, in der Küche stapeln sich Eierkartons und leere Einmachgläser, durch die Glastüren der im Gang aufgestellten Schrankwand sieht man schier endlose Mengen zusammengefalteter Textilien, Marmeladengläser mit Kompott, darüber Kartons, und an den Wänden lehnen Stapel alter Zeitschriften, die vom Boden bis unter die Decke reichen.

Ein Duell mit dem glamourösen Gespenst, in dem sich beide mit Paketband am Kopf befestigten Rehgeweihen beharken, mutet fast wie eine surreale Hommage an Vito Acconcis Schattenboxer an. Im Anschluss inszeniert der Künstler mit Bildern von Kim Basinger, Günter Grass und einer Geisha, die er aus Zeitschriften gerissen hat und zwischen Gabelzinken steckt, den einzigen Dialog des Films. Der moderne Minnesang vor einem grauen Fernsehschirm ist aber wenig romantisch. Mit John Bocks Stimme heult Kim Basinger: „Ich bin so alleine!“, worauf Günter Grass bereitwillig anbietet: „Ich habe ein Heim für Dich.“ Da will Kim Basinger sofort mitkommen. Ungläubig fragt Grass nach: „Willst Du nicht wissen, was ich alles habe? Ich habe 526 Tassen. Ich habe 396 Gabeln. Ich habe … “ Grass zählt noch unter anderem 8786 Zeitschriften, 795 Bücher, 10 Teppiche und 54 Stöcke auf. Beeindruckt von dieser Aufzählung, gesellt sich die Geisha dazu: „Kann ich auch mit?“ Grass ist großzügig – alle dürfen mit.

Seine ähnlich extensive und wertlose Sammlung nutzt dem Protagonisten wenig, er hat nur die Schattengestalt als stumme und antagonistische Gesellschaft. Er begibt sich auf eine beschwerliche, labyrinthische Kletterpartie durch den Schrank, dazu erklingt der Schlagerklassiker „Grau zieht der Nebel“ von Alexandra: „Könnt ich Dich nur fragen: was ist geschehen, dann werde ich Dir sagen, ich kann Dich verstehen.“ Er dringt in immer neue Schrankabschnitte vor, stößt eine Doppeltür auf und windet sich heraus und schleppt sich ins Badezimmer. Er setzt sich auf die Toilette, würgt und erbricht sich. Hinter ihm schiebt sich an einem immer länger werdenden Rohr ein Wasserhahn bedrohlich auf ihn zu, er spült sich ungerührt den Mund aus. Im Schlafzimmer schlägt der Einsiedler die Decke eines Doppelbettes zurück und legt eine erschreckend realistisch wirkende, mumifizierte Leiche frei. Mit dem Finger fährt er unter ihre Haut und findet grünen Schleim. Das führt zu einem Effekt wie ein Kurzschluss, die Leiche zuckt, aus ihr bricht eruptiv Schleim hervor, parallel dazu beginnt sich das Gespenst in der Küche wie in einem Anfall wild kreischend um die eigene Achse zu drehen. John Bock nimmt die Leiche beinahe zärtlich auf die Arme, wie sonst nur Hollywoodmonster ohnmächtige Blondinen, und verlässt die Wohnung. Vor einem lichtdurchfluteten Waldstück hält er inne. Während in der Wohnung das kreischende Gespenst tobt, verschwindet er mit der Leiche im Unterholz.

Indem er die Leiche befreit, bannt der Protagonist auch die Macht des Gespenstes. John Bock thematisiert in seiner Groteske die Notwendigkeit der Auseinandersetzung mit den inneren Dämonen und die Zerbrechlichkeit der eigenen Identität.

Andreas Schlaegel

Everything is black in the beginning. Then a match is lit, and the artist’s tense, unshaven face can be seen as he lights a cigarette. Everything goes dark again; only the embers that glow with every puff the artist takes are visible. The artist then turns on the light, cracks open an egg, rubs his hips with egg white, pauses for a moment, climbs laboriously from his bed, puts a cap on, and wraps himself in a bathrobe. When he sits down on an old couch and starts sewing buttons on a pillow, an uncanny figure played by the artist Adrian Lohmüller with a blackened face, a curly black wig, and a sequined garment is already sitting there. However, only the artist-hermit can be seen in the mirror standing in front of the couch, and when he notices this he jumps up. […]

Bock remains almost completely silent in Zezziminnegesang; he acts, but he explains nothing to the viewer or the other characters in the video. He tries to use a hammer and a chisel to break open a can of ravioli rather than to chip at a rock, and he continues to try until he succeeds by means of brute force. The meal turns out to be somewhat complicated because his spoon is stuck to a large living-room armchair. This means that to bring the food to his mouth, he must haul the chair in the air over his shoulder. Two spoonfuls are enough. After sipping some water out of a pipe taken from a stool made of tubular steel, the artist-hermit licks out an empty kitchen cabinet—possibly the only empty cupboard in the whole apartment—because everything else seems crammed full of things. Egg cartons and empty canning jars are stacked all over the kitchen. Through the glass doors of the wall unit in the hallway one also sees countless folded textiles, marmalade jars filled with stewed fruit, and cartons overhead, and old newspapers piled up to the ceiling lean against the walls.

The duel with the glamorous apparition, during which both parties battle each other wearing deer antlers taped to their heads with packaging tape, appears like a surreal homage to Vito Acconci’s shadow boxer (Shadow Play, 1970). Afterwards, the artist stages the film’s sole dialogue with pictures of Kim Basinger, Günter Grass, and a geisha that he has ripped out of newspapers and stuck between the prongs of forks. But the modern minnesong performed in front of a gray television screen is not very romantic. Basinger cries out with Bock’s voice, “I am so alone!” Günter Grass has a proposal ready for her: “I have a home for you.” Basinger wants to come along right away. Incredulous, Grass asks her, “Don’t you want to know what I have? I have 526 cups. I have 396 forks. I have . . .” Grass continues to count off 8,786 newspapers, 795 books, 10 carpets, and 54 canes, among other items. Impressed by this inventory, the geisha joins in: “Can I come, too?” Grass is generous: he says everyone can come along.

The protagonist’s extensive and worthless collection, however, does him no good, as his only company is the mute and antagonistic shadow figure, so he sets off on an onerous, labyrinthine climbing tour through the cabinet to the tune of Alexandra’s classic German pop hit “Grau zieht der Nebel.” Alexandra sings, “If I could only ask you what happened, I would tell you I understand.” Again and again, he makes inroads into new sections of the cabinet, flings open the double doors, winds his way back, and drags himself to the bathroom. He sits down on the toilet, retches, and then throws up. Behind him, a pipe to which a faucet is attached starts growing out of the wall and coming threateningly in his direction. Unphased, he turns on the tap and rinses out his mouth. In the bedroom, the artist-hermit pulls back the blanket of a double bed and exposes a horrifying mummified corpse. Probing its skin with his finger, he discovers a green slimy substance. The corpse then jolts as if it had short circuited. As slime oozes out of the corpse’s chest, the apparition in the kitchen simultaneously has a seizure and starts screeching and wildly flailing about in circles. Bock gently takes the corpse in his arms, as a Hollywood monster would do with a comatose blond, and leaves the apartment. He pauses at a sun-drenched piece of woodlands. While the screaming apparition clamors back in the apartment, he disappears with the corpse into the underbrush.

By freeing the corpse, the protagonist also exorcises the apparition’s power. Bock’s grotesque tale deals with the necessity of confronting one’s inner demons and with the frailty of one’s identity.

Andreas Schlaegel

Bock John 4166 4065 4055 4051 4059 11381JOHN BOCK, ZEZZIMINNEGESANG, 2006

MONICA BONVICINI, HAMMERING OUT (AN OLD ARGUMENT), 1998–2003

MONICA BONVICINI, HAMMERING OUT (AN OLD ARGUMENT), 1998–2003

MONICA BONVICINI, HAMMERING OUT (AN OLD ARGUMENT), 1998–2003

MONICA BONVICINI, HAMMERING OUT (AN OLD ARGUMENT), 1998–2003

Hammering Out (an old argument) © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2021. Courtesy of the artist. © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2021. Courtesy of the artist. 1998–2003In der Videoinstallation Hammering Out (an old argument) wird das Aufbrechen von Traditionen oder Konventionen offenbar wörtlich genommen. Man sieht den Arm einer Frau mit einem Vorschlaghammer auf eine weiße Wand einschlagen, bis das Mauerwerk frei liegt. Da auch die Projektionswand eine weiße Wand ist, ergibt sich zunächst ein Trompe-l’œil-artiger Effekt, bei dem die im Video dargestellte Wand ebenso exemplarisch attackiert wird wie jede andere Wand, die sich einem in den Weg stellt. Bonvicinis institutionskritischer Ansatz greift die Wand als ein generisches Stück Architektur an, das als weißer, neutraler, „jungfräulich“ kodifizierter Bildhintergrund dient, und bricht die Wand auf, um die Konstruktion bloß zu legen, und damit den ideologischen Unterbau. Sie enttarnt den Innenraum als kulturell festgelegten Ort, der in seiner Struktur Schmucklosigkeit, Kühle und Rationalität beinhaltet. Die glatten Wände umgrenzen einen Raum von intellektueller, maskulin geprägter Autorität, und damit der Repression, an dem sich die Mechanismen von Macht abzeichnen und den scheinbar neutralen Raum als ein von Irrationalität und Sexualität geprägtes Konstrukt darstellen. Dieser nunmehr mit Trostlosigkeit, Einsamkeit und Verlassenheit assoziierte Raum ist Ausdruck eines Machismo, wie er von einem der Überväter der architektonischen Moderne, Le Corbusier, in seinem Credo formuliert wurde: „Je crois en la peau des choses comme en celle des femmes“ („Ich glaube an die Haut der Dinge wie der von Frauen“) – ebenfalls der Titel von Bonvicinis 1999 entstandenen Installation I Believe in the Skin of Things as in that of Women.

Hammering Out (an old argument) ist somit der Angriff einer Frau auf die chauvinistische Vormachtstellung, die sich in der Architektur widerspiegelt, als Metapher für Geschlechter- und Klassentrennung, und ein Versuch, den Raum als Ort zurückzugewinnen und neu zu besetzen. Doch während der Hammer auf der Wand Verwüstungen anrichtet und durch die Schichten der Wand bricht, schafft er kein Fenster und auch keinen Ausweg, der aus dem Raum herausführte. Freigelegt wird lediglich das architektonische Mauerwerk, das zur Konstruktion einer undurchdringlichen Fassade aus repressiven Ideologien beiträgt.

Angela Rosenberg

The act of breaking with tradition and convention is apparently taken literally in the video installation Hammering Out (an old argument) (1998–2003). One sees a woman’s arm holding a sledgehammer that repeatedly smashes into a white wall until the underlying masonry is revealed. When projected onto a white wall, the video initially has a trompe l’oeil effect whereby the wall attacked in the video represents any wall that stands in one’s way. Bonvicini’s institutional critique assaults the wall as a generic piece of architecture—a background codified as white, neutral, and “virginal”—in order to break it open and reveal not only its construction, but also its ideological substructure. She exposes interior space as a culturally codified site with a structure that is austere, cold, and rational. The smooth walls define a space of intellectual, inherently masculine authority, as well as the repression delineated by mechanisms of power, which represent what appears to be neutral space as a construct characterized by irrationality and sexuality. Associated with bleakness, loneliness, and desolation, this space is an expression of machismo, as articulated in the credo of one of the father figures of architectural modernity, Le Corbusier: “I believe in the skin of things as in that of women”— which is also the title of Bonvicini’s installation from 1999.

Hammering Out (an old argument) is a woman’s attack on the chauvinistic supremacy that is reflected in architecture as a metaphor for the separation of sex and class—an attempt to regain the locus of space and to occupy it anew. However, although the hammer wreaks havoc on the wall and penetrates its different layers, it does not manage to create any window or exit from the space. The only thing revealed is the architectural stonework, which supports the construct of the impenetrable façade of repressive ideologies.

Angela Rosenberg

Bonvicini Monica 4167 4064 4065 4051 4059 11381MONICA BONVICINI, HAMMERING OUT (AN OLD ARGUMENT), 1998–2003

KLAUS VOM BRUCH, DAS ALLIIERTENBAND, 1982

KLAUS VOM BRUCH, DAS ALLIIERTENBAND, 1982

KLAUS VOM BRUCH, DAS ALLIIERTENBAND, 1982

KLAUS VOM BRUCH, DAS ALLIIERTENBAND, 1982

Das Alliiertenband © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2021. Courtesy of the artist and Electronic Arts Intermix, New York. © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2021. Courtesy of the artist and Electronic Arts Intermix, New York. 1982 vom Bruch Klaus 4178 4051 4063 4059 11381KLAUS VOM BRUCH, DAS ALLIIERTENBAND, 1982